TL;DR: The difference between stocks and bonds is straightforward. Stocks make you an owner in a company and are designed for long-term growth, but their values can fluctuate significantly. Bonds make you a lender to a government or corporation and focus on income and stability through regular interest payments. Most investors combine both to balance growth potential with portfolio resilience across market cycles.

In investing, stocks represent ownership in a business, while bonds represent a loan made to a government or corporation.

Crafting a successful investment portfolio begins with a simple but essential question: Do you want to own a business or lend to one? This distinction lies at the heart of how capital markets function and forms the foundation of nearly every investment decision.

Stocks and bonds are the two principal asset classes available to investors. While both can serve as vehicles for growing wealth, they differ in purpose, structure, return potential, and risk exposure. Understanding how they work and how they complement one another is crucial to building a portfolio that balances growth, income, and resilience through changing market conditions.

In this guide on the difference between stocks and bonds, we’ll examine how each asset works, how they behave under different economic conditions, and how to integrate them strategically to create a well-diversified, resilient portfolio.

Key Takeaways

- Stocks drive growth by providing ownership in businesses, but they come with higher volatility and larger price swings.

- Bonds provide stability through predictable interest income and capital preservation, though they are exposed to interest rate and inflation risk.

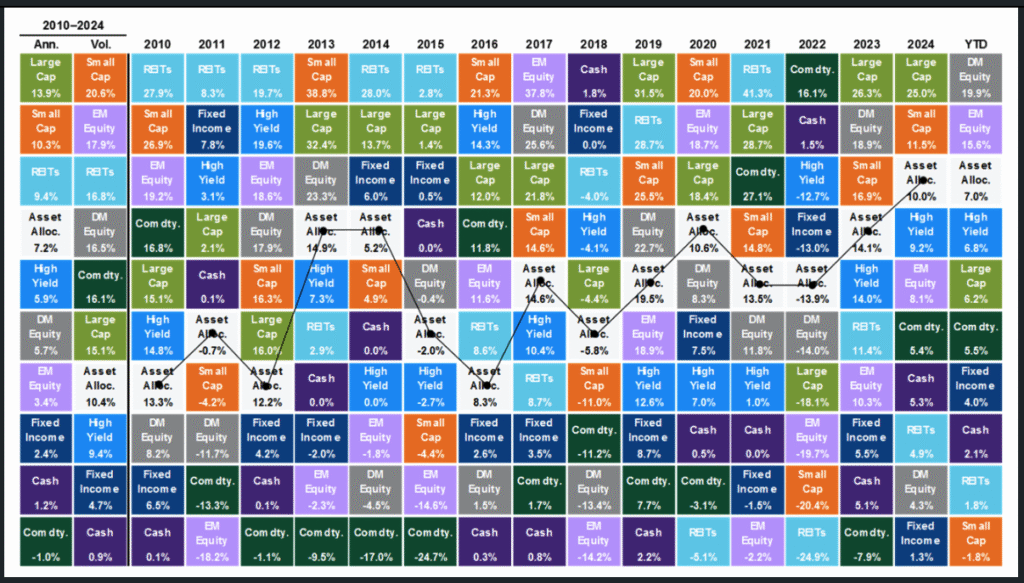

- Market cycles shift, causing stocks and bonds to outperform at different times depending on economic conditions.

- Balanced portfolios win by combining stocks and bonds in proportions aligned with time horizon, income needs, and risk tolerance.

1. Stocks vs. Bonds: The Key Differences at a Glance

Stocks and bonds differ not just in structure, but in the role they play inside a portfolio. One is designed to capture growth, the other to manage risk and provide income. Understanding these differences helps investors make allocation decisions that hold up across market cycles.

Feature | Stocks | Bonds |

|---|---|---|

What you get | Ownership stake in a company | Loan to a government or corporation |

Primary purpose | Long-term wealth growth | Income and capital preservation |

How returns are earned | Price appreciation and dividends | Interest payments and return of principal |

Volatility level | Higher, with larger price swings | Lower, but sensitive to interest rates |

Income predictability | Variable and not guaranteed | More predictable if held to maturity |

Risk exposure | Market, business, and valuation risk | Interest rate, credit, and inflation risk |

Time horizon fit | Best for long-term investors | Useful for income needs and shorter horizons |

Role in portfolio | Growth engine | Stabilizer and diversifier |

From a portfolio-construction perspective, stocks are the primary driver of long-term returns, while bonds help dampen volatility and provide liquidity during market stress. Neither asset class is inherently better. Their value depends on how and when they are used.

2. What Are Stocks?

Stocks, or equities, are financial securities that represent a claim on a company’s assets and earnings (represent ownership in a company). Publicly traded companies issue stock to raise capital for various business needs such as expansion, research, or debt repayment. Investors who purchase shares become partial owners and gain a claim on the company’s profits and assets.

There are two main types:

- Common stock, which usually grants voting rights and the potential for capital gains and dividends.

- Preferred stock, which provides fixed dividend payments and priority over common shareholders in the event of liquidation, but generally lacks voting rights.

From a capital markets perspective, equities sit at the top of the risk stack. Shareholders are last in line during liquidation but benefit disproportionately when a business compounds earnings efficiently. This asymmetric payoff structure is what makes stocks the primary source of long-term real returns across financial markets.

How Do Stocks Generate Returns?

Stock returns are a function of fundamentals, valuation, and capital distribution, with fundamentals doing most of the long-term work.

- Earnings and Cash Flow Growth: the primary driver of stock price appreciation is earnings and cash flow growth. When a company increases its profits, its intrinsic value rises, and investors are typically willing to pay more for its shares. For example, if a company grows its earnings per share (EPS) from $1.00 to $1.10 and maintains a constant price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 20, its stock price would rise from $20 to $22.

- Valuation Changes: stocks can also increase in value if the market assigns a higher valuation multiple, such as a higher P/E ratio. This often reflects optimism about the company’s future, favorable macroeconomic trends, or improving investor sentiment. However, valuation-driven gains can be short-lived if not supported by fundamentals.

- Dividends: many companies distribute a portion of their profits to shareholders through dividends. These regular payments provide a steady income stream and are especially appealing to income-focused investors. Dividend-paying companies are often seen as financially stable and committed to shareholder value.

What Drives Stock Volatility

Stock prices are influenced by a wide array of factors, including:

- Company-specific events: Earnings reports, leadership changes, competitive developments, and product launches.

- Macroeconomic indicators: Inflation rates, employment data, interest rates, and GDP growth.

- Investor sentiment: Market psychology, media coverage, and geopolitical developments.

These forces interact, often nonlinearly, causing prices to move sharply even when long-term fundamentals remain intact. As a result, short-term volatility in equities is not an anomaly but a structural feature of ownership claims on uncertain future cash flows.

3. What Are Bonds?

Bonds are debt instruments issued by governments, municipalities, or corporations to raise capital. When you buy a bond, you are effectively lending money to the issuer, who agrees to pay you regular interest (called a coupon) and repay the face value of the bond at maturity. Unlike stocks, bonds have explicit terms governing payment timing, priority, and repayment.

Bonds vary by:

- Issuer: Treasury, municipal, or corporate.

- Credit quality: Investment grade vs. high-yield.

- Maturity: Short, intermediate, or long-term.

- Interest structure: Fixed or floating rates.

In the capital structure, bonds sit above equities. Bondholders are paid before shareholders and have a legally enforceable claim on the issuer’s assets and cash flows. This seniority reduces risk relative to stocks but also caps upside, making bonds fundamentally defensive instruments rather than growth assets.

How Do Bonds Generate Returns?

Bond returns are driven by income, interest rates, and credit conditions, with income providing the bulk of expected returns.

- Coupon Payments: the primary source of bond returns is the coupon, or interest payment. This income stream is known in advance for fixed-rate bonds and forms the foundation of their appeal. For investors seeking predictable cash flows, especially over defined time horizons, coupon income is the central value proposition of bonds. For example, a $1,000 bond with a 4% coupon yields $40 annually. These payments provide steady, predictable income, which is a key benefit for conservative investors.

- Interest Rate Effects: bond prices move inversely to interest rates. When rates fall, existing bonds with higher coupons become more valuable, pushing prices up. When rates rise, bond prices decline as new issuance offers more attractive yields. The magnitude of this sensitivity is captured by duration, which measures how exposed a bond is to changes in rates.

- Credit Spread Changes: for corporate and non-government bonds, changes in perceived credit risk affect returns. Improving issuer fundamentals can compress credit spreads and lift prices, while deteriorating conditions widen spreads and reduce bond values. Credit risk is a key differentiator between investment-grade and high-yield bonds.

Investors may hold bonds to maturity for income and capital return or trade them for capital gains.

What Drives Bond Risk and Volatility

While bonds are typically less volatile than stocks, they are not risk-free. Their risks are more structural and macro-driven.

- Interest Rate Risk: Rising interest rates reduce the value of existing bonds.

- Credit Risk: The possibility that the issuer will default.

- Inflation Risk: Inflation reduces the real value of fixed interest payments.

These risks explain why bonds can underperform in inflationary or rapidly tightening regimes, despite their reputation for stability.

4. How Markets Shift Between Stocks and Bonds

Stocks and bonds don’t take turns outperforming by accident. They react differently to fear, optimism, policy shifts, and liquidity. Understanding why money moves between them is far more useful than memorizing economic labels.

At its core, the relationship is psychological as much as economic. Stocks thrive when investors feel confident about the future. Bonds gain relevance when certainty becomes scarce.

When Growth Feels Abundant

In periods when businesses are expanding, consumers are spending, and credit is easily available, stocks dominate. Investors are willing to accept volatility in exchange for upside. Future earnings look promising, capital is cheap, and risk-taking is rewarded.

Bonds still exist in these environments, but they are often treated as placeholders rather than destinations. Income matters less when opportunity feels plentiful.

What’s happening beneath the surface: Optimism pushes investors toward assets with unlimited upside and away from fixed returns.

When Confidence Cracks

When growth slows or uncertainty rises, markets reprice quickly. Earnings expectations weaken, volatility increases, and investors begin to care less about upside and more about survival. This is where bonds reassert their value.

High-quality bonds become attractive not because they offer excitement, but because they offer reliability. Predictable cash flows and legal claims matter more when outcomes feel uncertain.

What’s happening beneath the surface: Fear shifts demand from growth to certainty, and bonds benefit from that migration.

When Inflation Becomes the Problem

Inflation changes the game for both assets. Rising prices erode the real value of fixed payments, which is bad news for traditional bonds. Stocks can hold up better if companies have pricing power, but inflation also raises discount rates and pressures valuations.

This is one of the few environments where diversification feels less effective, and portfolio construction becomes more nuanced.

What’s happening beneath the surface: Investors struggle to protect purchasing power while navigating tighter financial conditions.

When Central Banks Take Control

Aggressive monetary tightening forces markets to adjust rapidly. Higher interest rates reduce bond prices and compress equity valuations. Liquidity matters more than narratives, and leverage becomes expensive.

In these phases, not all bonds behave the same. Shorter-duration and higher-quality bonds tend to hold up better than long-dated securities.

What’s happening beneath the surface: Policy risk replaces growth risk as the dominant force shaping returns.

5. Historical Cases: When Bonds Outperformed Stocks

While equities typically outperform over the long term, it’s important to understand that markets move in cycles, and each asset class has its moment. Bonds can outperform stocks during specific economic environments, especially when capital preservation, not growth, becomes the market’s priority. Let’s explore this dynamic more deeply through historical examples. These aren’t cherry-picked events, but structural shifts where investor psychology, policy response, and financial system behavior aligned in favor of bonds.

Case A: Global Financial Crisis (2008)

- Backdrop: The collapse of Lehman Brothers and the housing market caused a liquidity crisis. Equity markets fell by nearly 40%.

- Bond Response: U.S. Treasuries gained significantly. As panic grew, investors flocked to safety. Yields dropped and prices rose, with long-term government bonds returning over 20%.

- Key Insight: In a deflationary crisis, the flight to quality boosts government bond prices. They offer a cushion when equities are under severe stress.

Case B: Tech Bubble Collapse (2000–2002)

- Backdrop: Excessive speculation in dot-com stocks ended in collapse. The Nasdaq lost over 75% of its value.

- Bond Response: Investment-grade bonds provided steady income and limited drawdowns, with annual returns of 8-10%.

- Key Insight: Even when specific sectors crash, high-quality bonds deliver consistent income and act as capital stabilizers.

Case C: Yield Curve Inversion (2019)

- Backdrop: Market participants feared a recession as the yield curve inverted. Stock market growth slowed, and volatility spiked.

- Bond Response: Short-term Treasuries performed well, offering solid returns with minimal risk.

- Key Insight: Understanding the shape of the yield curve can help investors position defensively with bonds when equity momentum stalls.

Each of these scenarios illustrates a different role that bonds can play-from capital preservation to steady income to tactical protection-underscoring why they remain essential in most diversified portfolios.

6. Common Mistakes Investors Make With Stocks and Bonds

Most investors do not fail because they chose the wrong asset. They fail because they misunderstood the role each asset plays and reacted poorly when markets tested them. The mistakes below are not theoretical. They repeat every cycle.

Treating Stocks and Bonds as Competitors

A common error is viewing stocks and bonds as rivals, as if one must replace the other. In reality, they are complementary tools designed for different conditions. Stocks are meant to capture growth. Bonds are meant to absorb stress.

When investors abandon bonds entirely during strong equity markets or overload on bonds after a downturn, they often lock in poor timing decisions rather than improve outcomes.

What goes wrong: portfolios lose balance just when it is needed most.

Chasing Recent Performance

Investors tend to overweight whatever has performed well most recently. After long bull markets, portfolios drift toward stocks. After equity selloffs, bonds suddenly feel “safer” and more appealing.

This behavior usually results in buying high and selling low. Markets rotate faster than investor psychology adapts.

What goes wrong: returns suffer, even when the assets themselves perform well over time.

Ignoring Interest Rate Risk in Bonds

Many investors assume bonds are always stable. They are not. Long-duration bonds can experience significant price declines when interest rates rise, even if the issuer remains financially sound.

Holding bonds without understanding duration and rate sensitivity can introduce more risk than intended.

What goes wrong: investors are surprised by losses in assets they believed were defensive.

Overestimating Emotional Tolerance

Risk tolerance looks very different on paper than it does during real drawdowns. Investors often overestimate their ability to tolerate stock volatility and underestimate how quickly fear influences decisions.

A portfolio that is theoretically optimal but emotionally unsustainable will not survive a full market cycle.

What goes wrong: panic selling at precisely the wrong moment.

7. How Professionals Allocate Stocks and Bond

It’s one thing to know how stocks and bonds behave. It’s another to turn that knowledge into a structured, rules-based investment strategy. Large institutions-pension funds, university endowments, sovereign wealth funds-have to deliver consistent results over decades. They use tested frameworks to manage allocation, reduce behavioral risk, and adapt to changing markets. These approaches can guide individual investors too, especially those seeking discipline and long-term alignment with goals.

Balanced Allocation (50/50)

- This framework assigns equal weight to stocks and bonds.

- Rebalancing keeps the portfolio aligned with its risk profile, forcing investors to trim outperformers and buy lagging assets.

- It’s a simple but powerful approach for those seeking moderate growth with limited volatility.

Growth-Oriented Allocation (90/10)

- Aimed at younger investors, this strategy maximizes equity exposure for long-term capital appreciation.

- The small bond allocation acts as a behavioral buffer and liquidity source during downturns.

- Best suited for those with high risk tolerance and long investment horizons.

Risk-Parity Allocation

- Risk parity balances the portfolio by targeting equal risk contribution from each asset class, not equal capital weight.

- Because stocks are more volatile, the strategy often results in a higher allocation to bonds.

- Frequently used by institutional investors looking to optimize risk-adjusted returns.

Liability-Driven Investing (LDI)

- LDI is used by institutions and retirees to align bond maturities with future liabilities.

- For example, a retiree might purchase a ladder of bonds maturing annually to match withdrawal needs.

- This approach reduces reinvestment risk and improves predictability of cash flows.

These strategies demonstrate that asset allocation is not just about return optimization, it’s also about behavior management, risk control, and aligning investments with future needs.

Putting It All Together: Building a Resilient Portfolio

Stocks and bonds are not in competition. They are complementary tools in the pursuit of long-term financial success. Each asset class plays a unique and vital role: stocks drive growth by capturing the upside of economic expansion, while bonds provide stability, income, and protection during periods of uncertainty or market stress.

A resilient investment strategy is not built on predictions, but on preparation. By understanding the mechanics and behavior of both stocks and bonds, investors can construct portfolios that are not only diversified, but also aligned with their personal risk tolerance, time horizon, and financial objectives.

The true strength of a balanced portfolio lies in its ability to adapt across market cycles, participating in upside opportunities while remaining anchored during volatility. This balance helps smooth returns, reduce emotional decision-making, and increase the likelihood of achieving long-term goals.

Ultimately, successful investing isn’t about outsmarting the market day to day. It’s about crafting a durable plan, staying disciplined through both optimism and fear, and letting time and compounding do their work.

Be deliberate. Stay invested. Build with purpose.