Enterprise Value (EV) answers a simple but critical question: what does it really cost to own a business? Unlike market capitalization, which only reflects the value of a company’s shares, EV captures the full economic picture by accounting for debt, cash, and other financial obligations.

Because it reflects the value of the entire operating business, Enterprise Value is the metric investors, analysts, and acquirers rely on when comparing companies, evaluating valuation multiples, or estimating acquisition prices. It strips away differences in capital structure and focuses on what ultimately matters: the total value of the firm.

In this article, we’ll break down what Enterprise Value is, how it’s calculated, why it’s important, and how it’s used in financial analysis and investment decisions.

Key Takeaways

- Total business value: Enterprise Value (EV) measures the value of the entire company, not just its equity, making it a more complete valuation metric than market capitalization.

- Capital structure inclusive: EV includes debt, preferred equity, and minority interest while subtracting cash, allowing investors to assess companies regardless of how they are financed.

- Better company comparisons: By neutralizing differences in leverage and cash balances, EV enables more meaningful comparisons between companies with different capital structures.

- Valuation foundation: Enterprise Value is the basis for widely used multiples such as EV/EBITDA, EV/EBIT, and EV/Revenue, which are central to investment analysis and M&A.

What Is Enterprise Value?

Enterprise Value (EV) represents the total value of a company’s operating business. It reflects what an investor or acquirer is effectively paying for the firm’s core operations, independent of how the company is financed.

Unlike market capitalization, which only measures the value of equity, Enterprise Value includes debt and other claims on the business and subtracts cash that would be available to the buyer. This makes EV a more accurate measure of a company’s true economic value.

In simple terms, Enterprise Value measures the value of the business itself, while market capitalization measures only the value of the stock.

Enterprise Value Formula

Enterprise Value (EV) = Market Capitalization + Total Debt + Preferred Equity + Minority Interest − Cash and Cash Equivalents

This formula adjusts a company’s equity value to reflect all major claims on the business, while removing cash that reduces the effective cost of ownership.

Components of Enterprise Value Calculation:

- Market Capitalization: The total value of a public company’s outstanding common shares (Current Share Price × Outstanding Shares).

- Total Debt: Includes both short-term and long-term interest-bearing liabilities, such as loans, bonds, leases and other outstanding debt elements.

- Preferred Equity: Represents preferred shares that pay fixed dividends and have priority over common stock in liquidation.

- Minority Interest: The portion of subsidiaries not owned by the parent company but included in consolidated financials.

- Cash and Cash Equivalents: Highly liquid assets like cash reserves, bank deposits, and short-term investments, subtracted because they reduce the net cost to acquire the business.

Why Cash Is Subtracted and Debt Is Added

Enterprise Value is designed to measure the value of the operating business. Debt increases the cost of owning that business, while excess cash lowers it. By adjusting for both, EV allows investors to compare companies on a capital structure–neutral basis.

Why Enterprise Value Matters

✅ More Comprehensive Than Market Capitalisation

While market capitalization reflects only the value of a company’s equity, it overlooks crucial elements like debt and cash reserves. Enterprise Value delivers a fuller picture by accounting for all sources of capital, making it especially useful for analyzing companies with significant leverage or large cash holdings.

✅ Improves Comparability Across Companies

EV levels the playing field when comparing companies with different capital structures. Two companies might have similar market caps, but if one is heavily indebted and the other is debt-free, their Enterprise Values and investment risk profiles will differ significantly.

✅ Foundation for Key Valuation Multiples

Enterprise Value is the cornerstone of several essential valuation ratios used in financial analysis, investment banking, and M&A:

- EV/EBITDA – Evaluates a company’s value relative to its core operating performance, excluding non-cash expenses and capital structure.

- EV/EBIT – Measures value against operating income, helpful when depreciation or amortization skews EBITDA.

- EV/Revenue – Useful for early-stage, high-growth, or unprofitable companies where earnings metrics may not yet apply.

These multiples help investors and analysts assess a company’s performance, profitability, and valuation in a capital structure-neutral way.

✅ Critical for Investment and Acquisition Decisions

In both public market investing and M&A, decisions are made based on the value of the business, not just its stock price. Enterprise Value helps investors assess whether a company is overvalued or undervalued and helps acquirers estimate the total cost of a transaction.

Financial Ratios That Use Enterprise Value

Enterprise Value is most powerful when used in valuation multiples. These ratios compare the total value of a business to its operating performance, allowing investors to assess valuation without distortion from capital structure.

EV/EBITDA

EV/EBITDA is the most widely used enterprise value multiple. It compares a company’s total value to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization.

This multiple is especially useful because it focuses on operating profitability while excluding financing decisions and non-cash expenses. It is commonly used to compare companies within the same industry and to evaluate acquisition valuations.

EV/EBIT

EV/EBIT compares Enterprise Value to operating income after depreciation and amortization. This metric is useful when capital intensity matters, such as in manufacturing, utilities, or infrastructure-heavy businesses.

Because it includes depreciation, EV/EBIT can provide a more conservative view of valuation than EV/EBITDA.

EV/Revenue

EV/Revenue is often used for early-stage, high-growth, or unprofitable companies where earnings-based metrics are not yet meaningful.

This multiple helps investors compare valuation relative to top-line scale, particularly in technology, biotech, and emerging industries.

Why EV-Based Multiples Matter

Unlike equity-based multiples such as P/E, EV-based multiples reflect the value of the entire business. This makes them more reliable for comparing companies with different leverage, tax structures, or capital intensity.

How Is Enterprise Value Used?

Understanding enterprise value (EV) is critical across various areas of finance and investing. Here’s how professionals and companies apply it:

1. Investment Analysis

Who uses it: Institutional investors, portfolio managers, equity analysts, retail investors

How it’s used: EV is a key input for valuation multiples such as EV/EBITDA, EV/EBIT, and EV/Revenue. These metrics help investors determine whether a stock is overvalued or undervalued relative to its peers or the broader market.

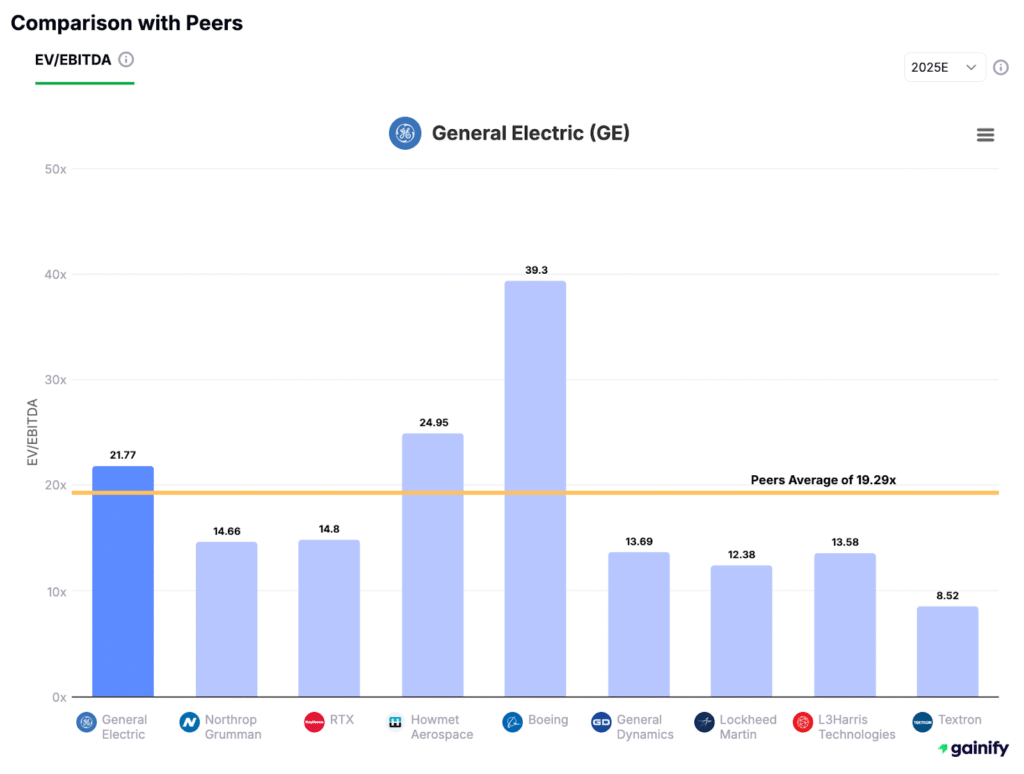

Example: General Electric (GE) vs. Peers (2025E EV/EBITDA)

Looking at the 2025 estimated EV/EBITDA multiples:

- GE trades at 21.77x, above the peer group average of 19.29x.

- Peers such as Northrop Grumman (14.66x), RTX (14.80x), and General Dynamics (13.69x) trade at significantly lower multiples.

- Boeing, on the other hand, trades at a much higher 39.3x, indicating a premium valuation.

This tells us that GE may be slightly overvalued relative to its peer average but still far below Boeing’s premium. Therefore, investors need to dig deeper — does GE deserve this valuation based on growth prospects, margins, or strategic positioning?

2. Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A)

Who uses it: Investment bankers, corporate development teams, private equity firms

How it’s used: In M&A, Enterprise Value is often the starting point for determining how much a company is worth. Buyers typically apply a valuation multiple — such as EV/EBITDA — to the target’s financials to arrive at an estimated EV. Once the EV is established, analysts work backwards to calculate the equity value, which reflects what the buyer would actually pay to shareholders.

Example: Let’s say an acquirer values a target at 10x EBITDA for a company, and the target is generating $250M EBITDA.

- Enterprise Value = 10 × $250M = $2.5B

- Debt = $400M

- Cash and other most liquid assets = $100M

- Equity Value = EV – Net Debt = $2.5B – ($400M – $100M) = $2.2B

In this case, $2.2B is what the acquirer would offer to shareholders. The EV represents the total valuation of the business; the equity value reflects the price shareholders receive after accounting for the company’s financial obligations.

3. Financial Modeling

Who uses it: Analysts, investment bankers, private equity professionals

How it’s used: Enterprise Value is a core component of discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis and leveraged buyout (LBO) models — two of the most widely used valuation techniques.

- In a DCF model, you project a company’s free cash flows and discount them back to present value. The result is its Enterprise Value, from which equity value is derived.

- In an LBO model, you forecast EV under different debt structures to estimate internal rates of return (IRR) for private equity sponsors.

Enterprise Value vs. Equity Value

When analyzing a company’s valuation, two terms frequently come up: Enterprise Value (EV) and Equity Value. While they are related, they serve different purposes and provide distinct perspectives on a business’s worth.

Side-by-Side Comparison

Feature | Enterprise Value (EV) | Equity Value (Market Cap) |

Includes Debt | ✅ Yes – Includes both short-term and long-term debt | ❌ No – Debt is not included |

Includes Cash | ❌ No – Cash and cash equivalents are subtracted | ✅ Yes – Cash remains part of shareholders’ assets |

Includes Preferred Equity | ✅ Yes – Treated as a senior claim similar to debt | ❌ No – Preferred equity is not part of common shareholder equity |

Includes Minority Interest | ✅ Yes – Added to reflect total value of consolidated subsidiaries not wholly owned | ❌ No – Excludes value attributable to minority shareholders |

Focus | Total firm value (debt + equity + other claims – cash) | Shareholder value (ownership of common equity only) |

Basis for Valuation Multiples | ✅ Yes – Used in EV/EBITDA, EV/EBIT, EV/Revenue, etc. | ❌ Rarely – Market cap-based multiples (e.g., P/E) are equity-specific |

Affected by Capital Structure | ✅ Yes – Sensitive to debt and cash levels | ❌ No – Pure reflection of stock price times shares outstanding |

Used in DCF and LBO Models | ✅ Yes – EV is central to intrinsic valuation frameworks like DCF and LBO | 🔄 Used after deriving enterprise value, to calculate implied equity value |

How Calculated | Market Cap + Total Debt + Preferred Equity + Minority Interest – Cash | Current Share Price × Total Outstanding Shares |

Limitations of Enterprise Value

While Enterprise Value is a powerful valuation metric, it is not universally applicable. Understanding its limitations is essential to avoid misinterpretation.

Not Ideal for Financial Institutions

Enterprise Value is less useful for banks, insurers, and other financial institutions. Debt is a core operating input for these businesses rather than a financing choice, which makes EV-based comparisons misleading.

Can Mislead for Cash-Heavy Companies

Companies with unusually large cash balances, such as mature technology firms, may appear artificially cheap on an EV basis. In these cases, EV can understate the value of the operating business if excess cash is not properly adjusted.

Sensitive to Accounting Differences

Enterprise Value relies on balance sheet inputs that can vary across accounting standards and jurisdictions. Differences in lease treatment, pension liabilities, or minority interest reporting can distort comparisons.

Does Not Capture Growth or Quality

EV measures value, not performance. A low EV multiple does not necessarily mean a company is attractive if growth prospects, margins, or competitive positioning are weak.

Common Misconceptions About EV

“Enterprise Value is just another name for market cap.”

❌ False. Market capitalization only reflects the value of a company’s equity. EV goes further by including other balance sheet items such as debt and subtracting cash, giving a more comprehensive picture.

“Cash doesn’t matter when valuing a business.”

❌ Incorrect. Cash reduces the effective cost to acquire a business. A company with a large cash balance will have a lower EV relative to its market cap.

“A higher EV always means a better company.”

❌ Not necessarily. A high EV might suggest a valuable business, but without context (e.g., EV/EBITDA or EV/Revenue), it says little about whether the company is fairly valued.

Final Thoughts

Understanding the distinction between enterprise value and equity value is essential for making informed financial and strategic decisions. Whether you’re conducting an acquisition analysis, building a financial model, or screening stocks.

Enterprise Value provides a holistic view of company valuation. Use it correctly, and you’ll gain a deeper, more nuanced understanding of how businesses are priced in the market.