The world of finance often presents itself as a realm of definitive figures, where every asset has an undeniable price tag. Yet, when it comes to assessing the true worth of a business, the landscape transforms into a fascinating blend of art and rigorous science. For business owners, investors, or those contemplating a strategic move, understanding a company’s value is not a mere academic exercise; it is the bedrock of intelligent decision-making and optimal capital allocation.

Too often, the quest for a single, magical valuation number can lead to frustration. The reality is that there’s no universal calculator offering a quick, definitive answer. Instead, expert financial analysis involves employing a suite of powerful methodologies, collectively known as business valuation methods. Each offers a unique lens through which a business’s intrinsic potential is viewed. This multifaceted approach ensures a comprehensive and reliable estimation of a company’s worth.

Finance experts consistently emphasize that company valuation is about more than numbers on a spreadsheet. It’s about understanding the core narrative of a company’s future, its strategic standing in the market, and the tangible resources it commands. This nuanced perspective allows for a more robust and defensible estimation of value, crucial for significant transactions, capital raising, or critical strategic planning, especially in mergers and acquisitions.

This article will guide you through the leading approaches used by top financial professionals to calculate business valuation. We will demystify the core models, explain their underlying philosophical logic, and illustrate how combining them creates a powerful framework for pinpointing a company’s true economic contribution. Prepare to gain the clarity needed to approach valuation with unparalleled confidence.

Method 1: The Income Approach – Discounting Future Value

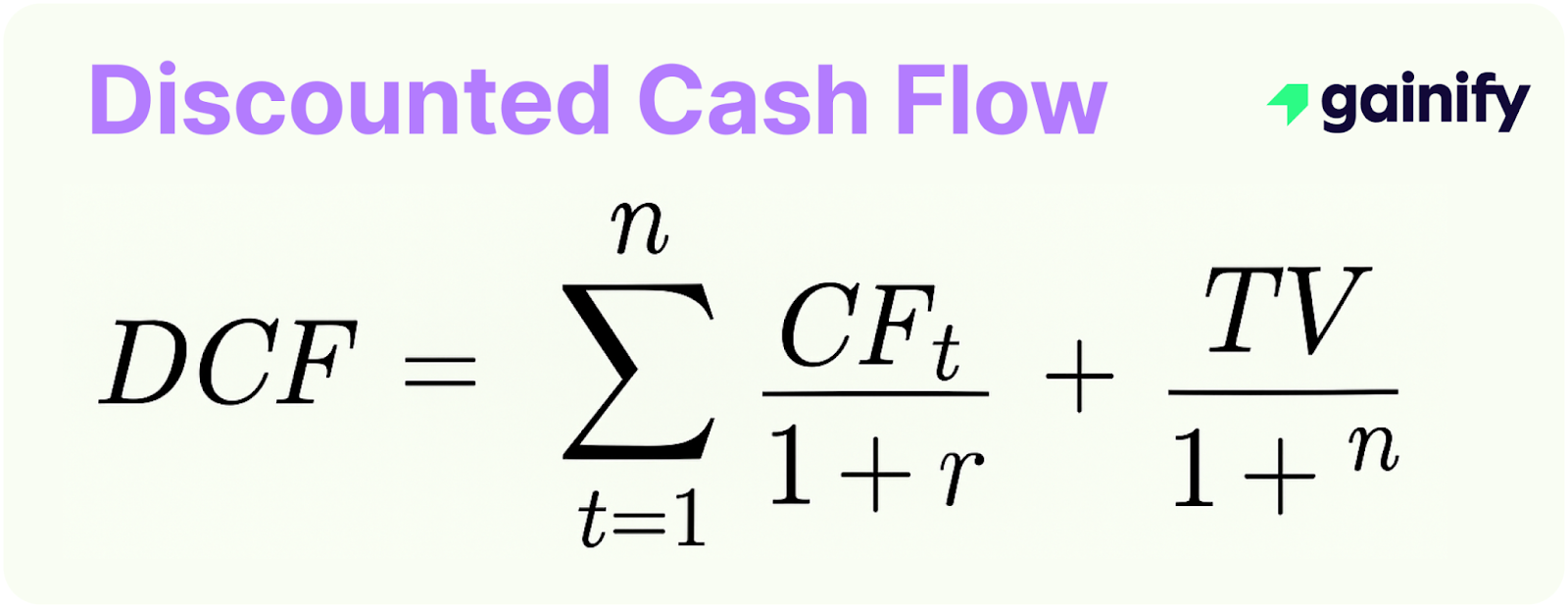

The Income Approach is a cornerstone among business valuation methods, primarily utilizing the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model. This approach is rooted in the fundamental principle that a business’s value today stems from the total of its expected future financial benefits, adjusted for the time value of money and inherent risk. It provides an income-based valuation, looking ahead to forecast the cash a business will generate over a specific period of time.

To perform a Discounted Cash Flow valuation, analysts meticulously project a company’s Free Cash Flow (FCF) for an explicit forecast period, usually five to ten years. FCF precisely represents the cash a business generates after covering all operating expenses and necessary capital investments, cash which is then available to all capital providers. This rigorous process involves detailed cash flow analysis, carefully considering anticipated future revenue and expected profit margins. Ultimately, forecasting this metric provides a direct assessment of a company’s intrinsic growth potential and its capacity to create value for its stakeholders.

Beyond this explicit forecast, a Terminal Value is calculated, representing the value of all cash flows extending indefinitely into the future. This is often derived using a perpetual growth model (Gordon Growth Model) or an exit valuation multiple approach based on future earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA). These future cash flows and the Terminal Value are then “discounted” back to their present value using the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC), which reflects the blended cost of a company’s equity and debt financing, influenced by the prevailing interest rate and broader economic conditions.

A distinct part of the Income Approach, suitable for mature companies, is the Dividend Discount Model (DDM). This model values a company based on the present value of its expected future dividend payments. For example, a stable dividend stock with consistent payouts might be valued by dividing the next year’s expected dividend by the difference between the required rate of return and the dividend growth rate. This highlights income-based valuation from a shareholder’s perspective, reflecting future distributions.

Method 2: The Market Approach – Benchmarking Against Peers

The Market Approach is another widely accepted methodology to calculate business valuation, relying on the principle of comparable transactions. This involves assessing a company’s worth by comparing it to similar businesses that have recently been sold (known as precedent transaction analysis) or whose valuations are publicly known (market-based valuations). The core tenet is that comparable assets should command similar prices in an efficient market, making this a crucial aspect of company valuation.

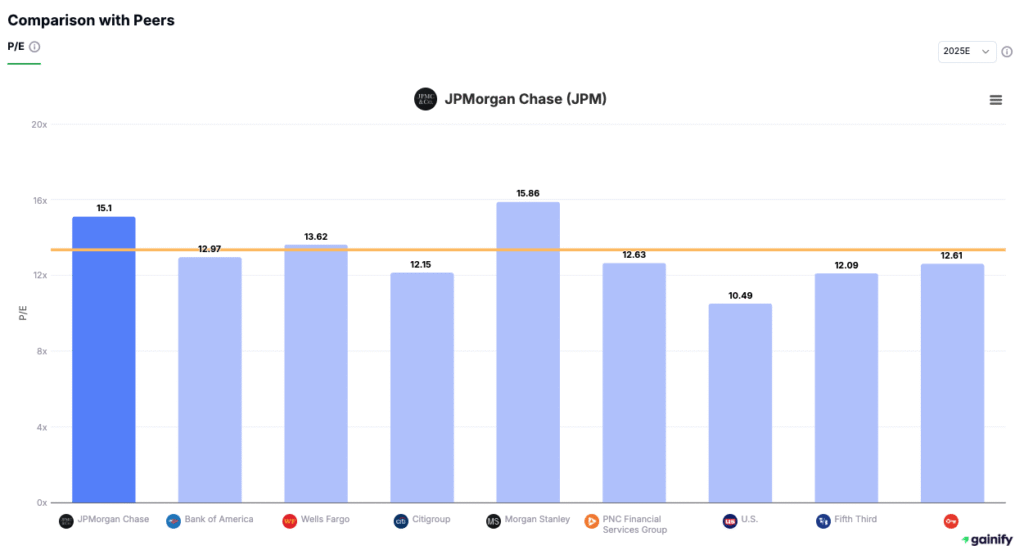

Analysts begin by identifying comparable companies that closely match the subject business in industry, operational model, size, and growth trajectory. This selection process is highly nuanced, as few companies are perfectly identical. Once a robust set of comparables is established, various financial valuation multiples are calculated from their current market valuations or past sale prices. Common multiples for publicly traded companies include Enterprise Value to Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization (EV/EBITDA), or Price Per Share to Earnings Per Share (the P/E ratio).

Other relevant multiples include the revenue multiplier, often used for early-stage or high-growth companies without significant earnings, calculated as market capitalization divided by annual sales or current sales. These derived multiples are then applied to the subject company’s own financial metrics to determine a range of implied values. For example, if comparable software companies trade at a revenue multiplier of 5x, and your company’s annual sales are $20 million, its implied value could be $100 million. This highlights how revenue-based valuations can provide insights into company per share value based on market trends.

While providing a crucial “market’s pulse check” on current valuations, this approach is inherently limited by the availability of truly comparable companies. It excels at reflecting prevailing market sentiment and macro trends but may not fully capture the unique strategic advantages or disadvantages of the subject business that an intrinsic valuation like DCF might uncover.

Method 3: The Asset Approach – Valuation Based on Tangible Holdings

The Asset Approach to business valuation focuses on the underlying resources controlled by a company. This asset-based valuation method assesses the business’s worth based on the fair market value of its total assets, subtracting its total liabilities. It is particularly relevant for asset-heavy businesses, holding companies, or scenarios where liquidation value is being considered. This is often seen in sectors involving physical assets like real estate or manufacturing.

This methodology often involves meticulously valuing tangible assets such as real estate, specialized machinery, and inventory at their current fair market value, which can differ significantly from their historical book value on the balance sheet. For highly specialized assets or intellectual property like patents and trademarks, independent appraisals may be necessary to determine an accurate cash value analysis. The reported shareholders’ equity on the balance sheet provides a starting point, but an asset-based valuation adjusts for true market values.

While offering a clear assessment of a company’s breakup value, the Asset Approach generally provides a conservative company valuation for a “going concern” business that is expected to continue operating and generating profits. This is because it often does not adequately account for the company’s future earning potential, its operational synergies, or the value embedded in its established customer relationships. It is most useful as a “floor valuation” or as a check on other methods, rather than a standalone valuation for a vibrant, operating enterprise seeking potential for growth.

Beyond Formulas: The Art of Valuation

While the quantitative methodologies discussed provide robust frameworks for calculating business valuation, a true expert understands that valuation is never solely about plugging numbers into formulas. Each approach carries inherent assumptions and sensitivities, and the choice of method often depends on a variety of factors, including the specific purpose of the valuation itself. A valuation for a strategic acquisition in mergers and acquisitions, for example, might prioritize future synergies not captured by current market-based valuations or historical precedent transactions.

Consider how crucial qualitative factors subtly yet profoundly influence perceived value. A company distinguished by an exceptional, innovative management team, a unique competitive advantage, or a highly loyal customer base often commands a higher company valuation. This occurs even when compared to peers with similar current financial metrics but weaker intangible assets. These elements are not directly represented in a P/E ratio but are fundamental to the narrative of future revenue growth and risk profile.

Furthermore, the very act of valuation is frequently embedded within a broader strategic context or negotiation. Whether the objective is a sale, a merger, or attracting new investment, the final agreed-upon value is always influenced by the bargaining power, information asymmetry, and the distinct strategic objectives of all parties involved. A buyer might intrinsically value a company differently than a seller, each naturally emphasizing aspects that fortify their respective positions. This requires a professional valuation or third-party assessment.

Therefore, the discerning financial professional combines quantitative rigor with astute qualitative insight. They select the most appropriate methods based on the specific situation, apply thoughtful adjustments informed by market realities, and interpret the results within the broader context of the business’s industry, competitive landscape, and strategic purpose. This informed judgment and seasoned perspective, supported by diligent record keeping often aided by online accounting software, ultimately transforms raw financial data into truly actionable insights.

Final Insights for Pinpointing Business Worth

Assessing a company’s value is a sophisticated endeavor, demanding a fusion of rigorous financial models and insightful qualitative analysis.

- Valuation is Purpose-Driven: The “right” valuation number is fundamentally shaped by its specific objective.

- No Single Truth: There is no one absolute valuation; a robust analysis involves triangulating a range of values from multiple methodologies.

- Future Earnings Drive Value: For most operating businesses, anticipated future cash flows are far more critical than historical performance or current asset book values.

- Market Context is Essential: Comparing a business to truly similar companies using relevant market multiples provides crucial external validation.

- Qualitative Factors Hold Immense Sway: Beyond financial statements, elements like management quality, brand strength, and competitive advantages are paramount to long-term value.

- Assumptions are Core to the Model: All valuation methods rely on projections and assumptions about the future, necessitating careful judgment and transparent disclosure.