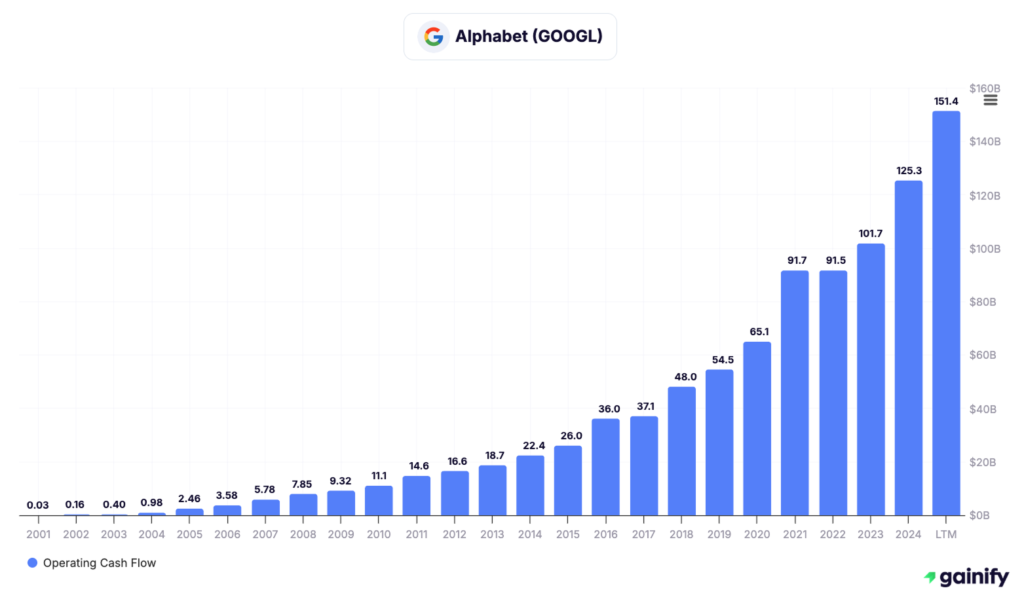

What is operating cash flow? Operating Cash Flow (OCF), also known as cash flow from operations, is one of the most important financial metrics used to assess a company’s financial health and operational strength. It measures the actual cash generated by a business from its core operations during a specific accounting period.

This cash flow is vital because it shows whether a company can sustain its activities, invest in growth, repay obligations, and potentially return capital to shareholders – all without depending on external financing activities.

Unlike net income, which is shaped by accounting conventions and non-cash items such as depreciation or amortization, OCF focuses exclusively on real cash movements. This makes it a more accurate and transparent indicator of a company’s ability to generate liquidity from its business model.

In essence, operating cash flow provides a clear and practical lens through which to view the sustainability of a company’s business operations and its capacity to deliver long-term value.

Key Takeaways

- Operating performance: Measures cash generated from a company’s core operating activities over a defined period

- Cash-based insight: Reflects actual cash movements rather than accrual-based earnings

- Liquidity assessment: Helps evaluate a company’s ability to fund operations, service obligations, and reinvest internally

- Analytical foundation: Forms the basis for free cash flow calculations and cash-driven valuation models

What Is Operating Cash Flow?

Operating Cash Flow represents the cash a company generates from its core business activities during a specific accounting period. These activities include producing and selling goods or services and covering operating costs such as payments to suppliers, employees, and tax authorities.

Operating cash flow focuses on cash movements directly related to operations. It excludes cash flows from investing activities and financing activities, which allows the metric to isolate cash performance from ongoing business functions.

In practical terms, Operating Cash Flow helps answer questions like:

- Can the business generate enough cash to fund day-to-day activities?

- Is it self-sufficient or dependent on borrowing?

- How effectively is it converting sales and profits into real cash?

By emphasizing operational cash generation, operating cash flow helps assess whether a business can maintain daily operations, support growth initiatives, and meet financial obligations using internally generated cash.

What Is Operating Cash Flow?

Operating Cash Flow is typically found in the first section of the statement of cash flow, titled Cash Flows from Operating Activities, which is part of a company’s three core financial statements (alongside the income statement and balance sheet).

For publicly traded companies, operating cash flow is disclosed in quarterly and annual financial reports, including Form 10-Q and Form 10-K filings. These disclosures provide investors and analysts with standardized and comparable cash flow information across reporting periods.

Operating Cash Flow Formula

Operating Cash Flow can be calculated using two standard approaches: the indirect method and the direct method. Both methods produce the same operating cash flow figure, but they differ in how cash movements are presented.

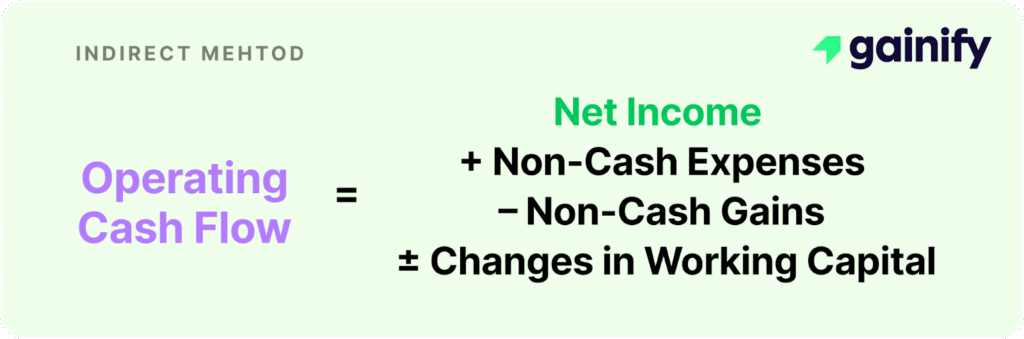

1. Operating Cash Flow Calculation: Indirect Method

The indirect method begins with net income, as reported on the income statement, and adjusts it for non-cash transactions and changes in working capital. This approach is widely used in financial reporting because it reconciles net income to actual cash generated from operations, providing a bridge between accrual accounting and cash accounting.

Operating Cash Flow Formula (Indirect Method)

Operating Cash Flow (OFC) = Net Income + Non-Cash Expenses – Non-Cash Gains +/- Changes in Working Capital

Where:

- Non-cash expenses include items such as depreciation, amortization, stock-based compensation, and deferred taxes. These expenses reduce net income but do not represent actual cash outflows, so they are added back.

- Non-cash gains typically arise from asset sales or investment revaluations. Because these gains increase net income without generating operating cash, they are removed from the calculation.

- Changes in working capital reflect movements in current assets and current liabilities, including accounts receivable, inventory, and accounts payable. These changes affect the timing of cash inflows and outflows and are captured on the balance sheet.

Together, these adjustments convert accrual-based net income into cash generated from operating activities, which is the core purpose of operating cash flow.

Example: Calculating Operating Cash Flow Using the Indirect Method

Let’s say a company reports the following financial data for the year:

- Net Income: $1,200,000

- Depreciation (non-cash expense): +$250,000

- Gain on Sale of Equipment (non-operating gain): –$50,000

- Increase in Accounts Receivable: –$100,000

- Decrease in Inventory: +$80,000

- Increase in Accounts Payable: +$70,000

Now, apply the indirect method formula:

OCF = $1,200,000 + $250,000 – $50,000 – $100,000 + $80,000 + $70,000 = $1,450,000

This method provides an insightful view into how net income translates into actual cash, revealing the underlying liquidity of a business beyond accounting profits. It’s particularly useful in identifying whether earnings are supported by real cash flows.

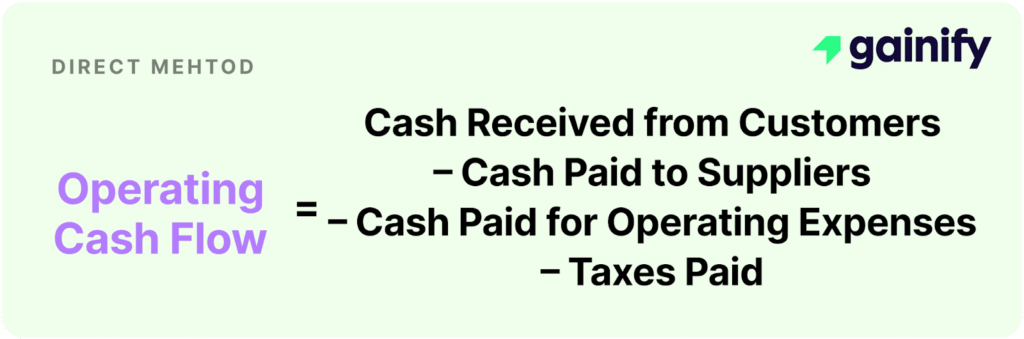

2. Operating Cash Flow Calculation: Direct Method

The Direct Method calculates Operating Cash Flow (OCF) by directly identifying and summing actual cash inflows and outflows resulting from a company’s day-to-day operations. Unlike the indirect method, it does not start with net income. Instead, it presents a straightforward breakdown of cash transactions, offering a more intuitive view of how cash moves through the business.

Cash Flow Components Included in the Direct Method

The direct method typically includes the following operating cash items:

- Cash received from customers

- Cash paid to suppliers

- Cash paid to employees

- Cash paid for rent, utilities, interest, and taxes

Operating Cash Flow Formula (Direct Method)

Operating Cash Flow (OFC) = Cash Received from Customers − Cash Paid to Suppliers − Cash Paid for Operating Expenses – Taxes Paid

Example: Calculating Operating Cash Flow Using the Direct Method

Let’s say a company reports the following financial data for the year:

- Cash received from customers: $2,000,000

- Cash paid to suppliers: –$600,000

- Cash paid for salaries and wages: –$400,000

- Cash paid for taxes: –$100,000

🔢 Now, apply the direct method formula:

Operating Cash Flow = $2,000,000 – $600,000 – $400,000 – $100,000 = $900,000

While the direct method provides a highly transparent view of operational cash inflows and outflows, it is less commonly used in external financial reporting. This is largely due to the data-intensive nature of the method, as it requires companies to track and categorize each individual cash transaction – something not typically emphasized in traditional accrual-based accounting systems.

Operating Cash Flow vs. Net Income

Metric | Includes Non-Cash Items | Reflects Working Capital | Primary Use |

Net Income | ✅ Yes | ❌ No | Profitability Measurement |

Operating Cash Flow | ❌ No | ✅ Yes | Liquidity & Cash Health |

Operating Cash Flow and net income are both key financial metrics, but they measure different aspects of a company’s financial performance.

Net Income is derived from a company’s income statement and includes both cash and non-cash items, such as depreciation, amortization, and changes in deferred taxes. It also reflects the effects of accounting choices and accruals.

Operating cash flow focuses on cash generated from core operating activities. It adjusts net income for non-cash items and incorporates changes in working capital, providing insight into how much cash the business actually produces during the period.

Understanding the distinction between Operating Cash Flow (OCF) and Net Income is essential for accurate financial analysis. While both are key financial metrics, they serve different purposes and rely on different components.

Key Insight: OCF is often considered more reliable than net income for assessing a company’s ability to generate cash, as it is less influenced by accounting policies.

What Is Operating Cash Flow Yield?

Operating Cash Flow Yield is a financial ratio that measures a company’s ability to generate cash relative to its market valuation. It is commonly used to evaluate how efficiently a company generates cash compared to the price investors are paying for its equity.

This metric is especially useful when comparing companies across industries or market capitalizations, as it focuses on cash generation rather than accounting earnings.

Operating Cash Flow Yield Formula

Operating Cash Flow Yield = Operating Cash Flow ÷ Market Capitalization

How Operating Cash Flow Yield Is Used

Operating cash flow yield helps analysts and investors:

- Assess valuation levels by identifying companies with strong cash generation relative to market value

- Compare operating efficiency across similar companies or sectors

- Evaluate investor expectations embedded in a company’s share price

Example: Operating Cash Flow Yield

Example: If a company generates $500 million in OCF and has a market capitalization of $5 billion:

OCF Yield = $500M / $5B = 10%

A higher OCF yield suggests strong cash-generating ability and potential undervaluation, whereas a lower yield could indicate weak fundamentals or overvaluation.

Why Operating Cash Flow Is Important

✔ Reflects Actual Cash Performance: OCF represents the real cash flowing in and out from business operations, offering a clear picture of financial viability.

✔ Reduces Accounting Noise: Unlike net income, OCF isn’t distorted by non-cash expenses or accrual-based accounting.

✔ Indicator of Sustainability: Consistent positive OCF signals a well-managed business with sufficient cash to cover liabilities and fund growth.

✔ Essential in Valuation Models: OCF is a core component of DCF (Discounted Cash Flow) models used by analysts and investors to estimate intrinsic value.

✔ Supports Dividend Assessment: Helps determine whether a company can sustain or grow dividend payouts over time.

Limitations and Considerations

⚠ Short-Term Volatility: Working capital (current assets or current liabilities) swings (e.g., inventory buildup or receivable delays) can temporarily distort OCF.

⚠ Does Not Include CapEx: OCF does not account for capital expenditures, which are vital for evaluating long-term sustainability and free cash flow.

⚠ Requires Context: OCF should be evaluated alongside metrics like Free Cash Flow, EBITDA, and ROIC for a complete financial picture.

⚠ Industry-Specific Benchmarks: OCF benchmarks vary widely. Asset-light industries may report higher ratios compared to capital-intensive sectors like manufacturing or energy.

Conclusion

Operating Cash Flow is a cornerstone of financial analysis and strategic decision-making. It offers a clear view of a company’s ability to convert core operations into real cash, providing a more reliable benchmark than net income.

Investors, CFOs, and financial analysts rely on OCF to:

- Evaluate business sustainability

- Screen for fundamentally strong investments

- Assess capital efficiency and profitability

When used in conjunction with complementary ratios like Free Cash Flow Yield, ROIC, and EBITDA margins, OCF becomes a powerful tool for identifying companies with robust financial health and long-term value potential.