In the relentless rhythm of the stock market, every investor grapples with a core question: Where does true value reside? Is it etched in the bold promises of tomorrow, in companies poised for exponential future revenue growth, fueled by cutting-edge innovation and ambition? Or is it quietly waiting in the present, within established businesses whose intrinsic worth the market currently undervalues, offering a serene calm amidst the financial storm? This profound duality defines the investment world’s most enduring debate: what is growth vs. value investing? Understanding these philosophies is not merely academic; it is foundational to constructing a resilient and profitable investment strategy.

For generations, astute investors have pondered this question: Do you chase the high-flying innovators expected to achieve explosive future earnings potential, or do you patiently seek out solid businesses currently trading below their true worth? This isn’t a new riddle. Legendary figures have built fortunes on both sides, proving that enduring success can emerge from either path, even across vastly different economic cycles. Your choice between growth investing and value investing shapes every aspect of your investment decision, from individual stock selection to how you construct your entire investment portfolio.

At its core, this isn’t a competition of “better” or “worse” but a difference in perspective on where genuine opportunity truly lies and how capital markets actually function. One philosophy champions the visionaries, betting on future dominance and the power of compounding earnings explosions. The other, deeply rooted in rigorous fundamental analysis, meticulously uncovers present-day bargains, ensuring a margin of safety. Both have delivered remarkable results across various market conditions, yet they respond very differently to shifts in market sentiment, changes in interest rates, and broader market dynamics. Recognizing these nuances is the first crucial step towards building a resilient and profitable investment portfolio.

Delving into what is growth vs. value investing offers essential insight into how major global markets operate. These philosophies are fundamental tools, not only for individuals managing their investment risk but also for understanding the strategic decisions businesses make. This guide aims to clearly explain the core principles behind each approach, illuminate their typical characteristics and historical performance, and provide the insights needed for an informed investment decision in today’s complex financial landscape.

What is Growth Investing? Chasing Tomorrow’s Innovators

Growth investing is an investment strategy fundamentally focused on identifying companies that are expected to grow at an above average rate compared to the overall market. These companies typically reinvest most of their earnings back into the business to fuel further expansion, rather than paying out dividends. Investors pursuing growth investing are primarily interested in future earnings potential and revenue expansion, even if the company’s current share price reflects a high valuation. This approach often prioritizes qualitative factors like innovation, strong company management, and a clear vision.

Key characteristics of a growth stock and companies favored by growth investors often include:

- High Growth Rates: These companies consistently show strong historical and projected increases in revenue and earnings. They are often in the early to middle stages of their growth curve, aiming for rapid expansion.

- Innovative Products or Services: They typically operate in rapidly expanding industries or have disruptive technologies that reshape existing markets. Common sectors include technology companies, biotechnology, cloud computing, and areas leveraging artificial intelligence.

- High Valuation Metrics: Because their value is tied to future potential, growth stocks frequently trade at higher price-to-earnings ratios (P/E ratio), price-to-sales (P/S), or other financial metrics compared to the broader market or their industry peers. The assumption is that strong future growth will justify these higher current stock prices.

- Low or No Dividends: Growth companies typically retain and reinvest a large portion, if not all, of their earnings back into the business. This capital is used to fund research and development, acquisitions, or market expansion. This is a core aspect of their capital allocation strategy aimed at maximizing capital appreciation.

- Competitive Advantage: They possess durable competitive advantages, often called an “economic moat”, such as powerful brands, proprietary technology, or network effects, which protect their future cash flows.

Examples of Growth Companies

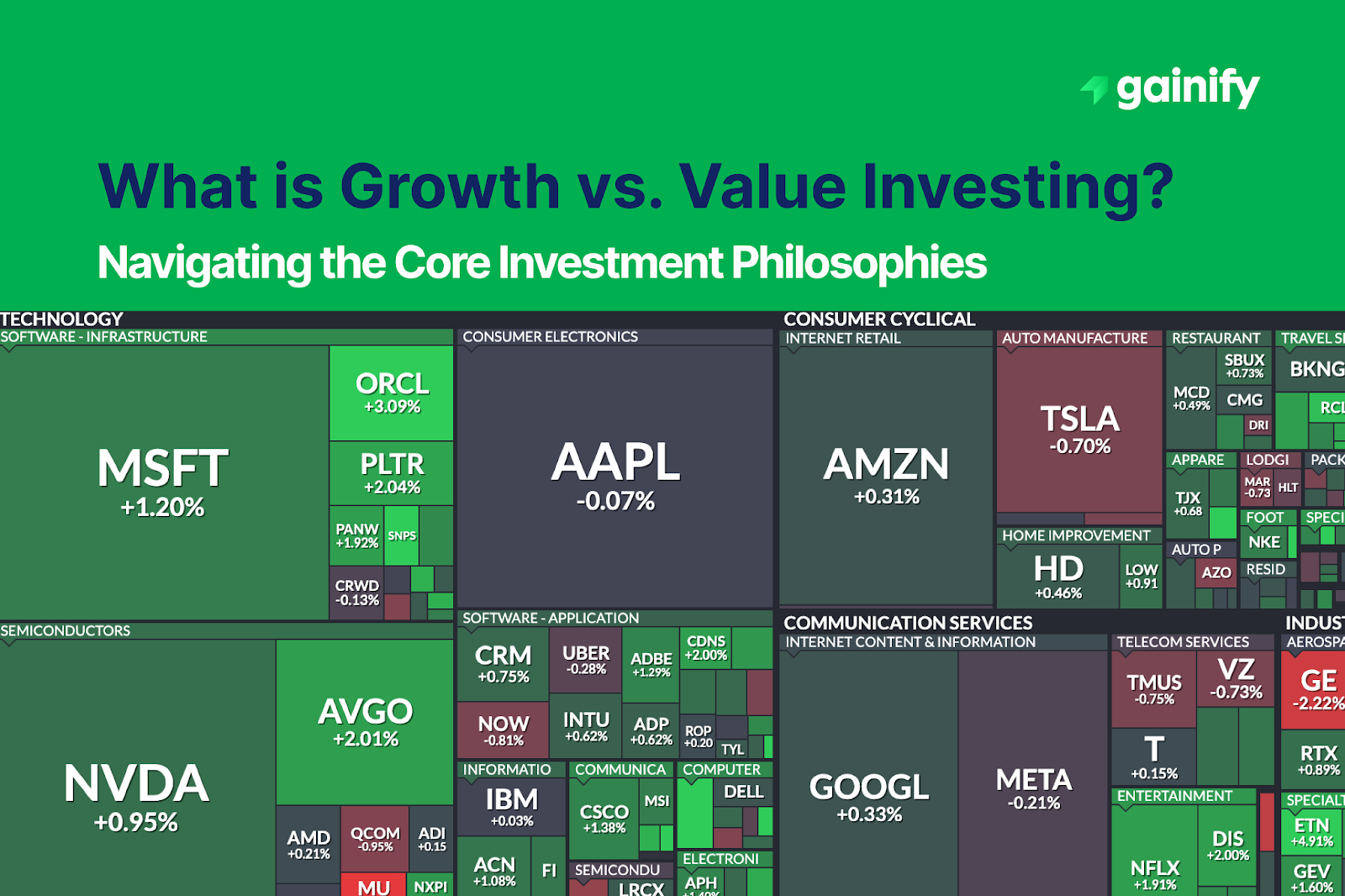

Historically, the landscape of growth stocks is dotted with companies that defied conventional valuation metrics, prioritizing aggressive expansion and future dominance. Think of Amazon.com Inc (AMZN) in its formative years. For a long time, it reinvested nearly every dollar back into infrastructure, fulfillment centers, and new ventures like Amazon Web Services, famously generating little to no profit while its revenue growth soared. Investors bought into the vision of massive future potential, willing to accept a high share price relative to current earnings. More recently, NVIDIA (NVDA) perfectly embodies the growth archetype. Its commanding lead in the specialized chips that power artificial intelligence applications has driven incredible stock price appreciation, fueled by massive reinvestment in research and development to stay ahead in a rapidly expanding market, despite high price-to-earnings ratios.

These technology stocks showcase how prioritizing capital appreciation through relentless innovation, even with a seemingly high PE ratio, defines growth investing. Beyond these giants, other compelling examples include innovative biotechnology firms developing breakthrough treatments, rapidly scaling software-as-a-service (SaaS) companies, or disruptive players in new energy sectors that promise significant future cash flows. Growth investors are continually on the hunt for the “next big thing”, prioritizing potential over present affordability and betting on future market leadership, often less concerned with the current PE ratio if expected returns from future growth are substantial.

What is Value Investing? Seeking Undervalued Gems

Value investing is an investment strategy centered on identifying companies trading for less than their intrinsic value. These companies are often overlooked, out of favor, or operating in industries facing temporary challenges. Value investors believe the market sometimes misprices securities, creating opportunities to buy quality businesses at a discount. This approach heavily relies on fundamental analysis and often involves detailed calculations using models like the discounted cash flow (DCF) or dividend discount model to estimate intrinsic worth.

Key characteristics of a value stock and companies favored by value investors often include:

- Low Valuation Metrics: They typically trade at lower price-to-earnings ratios (P/E ratio), price-to-book (P/B) ratios, or have higher dividend yields compared to the market average or their industry peers. These financial metrics and financial ratio analyses signal a potential bargain. Cash flow ratios are also a key focus.

- Established Businesses: These are often mature companies in stable, sometimes “boring” industries. They might be experiencing a temporary setback, or simply being ignored by the broader market, which is more drawn to growth stories. A large, established financial institution like JPMorgan Chase, for example, often exhibits characteristics that appeal to value investors, despite its scale.

- Strong Financial Fundamentals: Despite a low share price, they possess solid balance sheets, consistent cash flow, and a history of profitability. Value investors seek companies with genuine underlying business strength and strong financial fundamentals.

- Regular Dividends: Many value companies distribute a significant portion of their earnings to shareholders as dividends, providing a steady income stream.

- “Margin of Safety”: A core concept popularized by Benjamin Graham, meaning value investors seek to buy a stock at a price significantly below its calculated intrinsic value. This “cushion” provides protection against potential misjudgments or unexpected challenges and is a cornerstone of risk management.

Examples of Value Companies

Legendary investor Warren Buffett, through Berkshire Hathaway, is the most famous proponent of value investing. His portfolio often includes established businesses that are temporarily out of favor, such as insurance companies (e.g., GEICO), consumer goods giants (e.g., Coca-Cola), or strategically important energy firms which he acquires when he believes they are trading below their true worth. Other examples of value stocks might include financially sound industrial companies trading at low multiples during a cyclical downturn, or undervalued banks with strong balance sheets like Morgan Stanley. Additionally, certain consumer discretionary businesses experiencing temporary headwinds but strong long-term prospects often catch the eye of value investors. They continually look for a bargain, prioritizing current affordability and financial fundamentals, viewing market pessimism through the lens of behavioral finance as a source of opportunity. Ultimately, they aim to benefit from the market premium that accrues when the market eventually recognizes the company’s true intrinsic worth.

Key Differences and Performance Dynamics: Growth vs. Value

The distinction between growth vs. value investing extends beyond just their focus; it encompasses how they typically behave across different market environments. This comparison is often studied in factor investing, where “value” and “growth” are considered distinct factors that drive returns. Understanding these investment approaches is crucial for portfolio construction.

Feature | Growth Investing | Value Investing |

Primary Focus | Future earnings potential, revenue growth, innovation, market share expansion. | Current intrinsic value, undervalued assets, financial stability. |

Typical Companies | Younger, innovative, disruptive, often in technology stocks or biotech. | Mature, established, often in traditional industries (e.g., industrials, financials, consumer staples). |

Valuation Metrics | High price-to-earnings ratios, high price-to-sales ratios, high PEG ratio. | Low price-to-earnings ratios, low price-to-book ratios, high dividend yields. |

Dividends | Low or no dividends; profits are reinvested for growth. | Often pay consistent dividends; less reinvestment. |

Risk Profile | Can involve higher investment risk due to reliance on future projections and sensitivity to interest rates. Prone to growth traps. | Aims for lower risk due to “margin of safety”; prone to value traps if businesses decline permanently. |

Market Sensitivity | Tends to perform well in bull markets, periods of low interest rates, and strong economic expansion. Index examples include the Russell 1000 Growth Index or the S&P 500 Growth Index. | May outperform during bear markets, economic recoveries, periods of high inflation, or rising interest rates. Index examples include the Russell 1000 Value Index or the S&P 500 Value Index. |

Analytical Lean | Focus on future trends, market size, innovation, and qualitative factors. | Heavy reliance on fundamental analysis, quantitative factors like cash flow and balance sheet strength. |

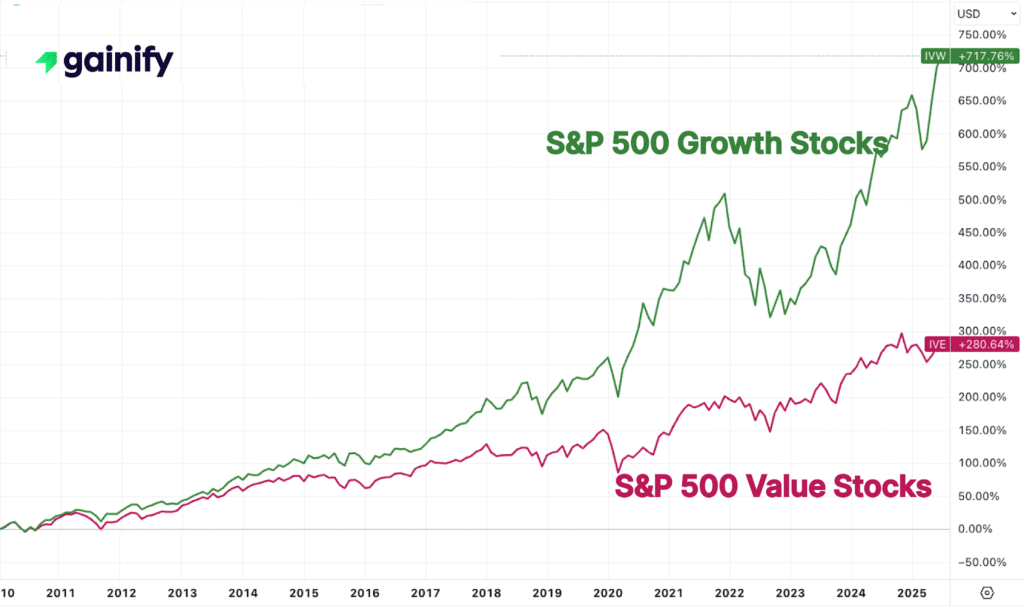

The performance of these styles is cyclical. During periods of low interest rates and strong technological advancement, growth stocks often lead the market, as future earnings are discounted less heavily. Conversely, when interest rates rise or during an economic recession or market downturn, the stability and present cash flow of value stocks can become more appealing. This market dynamics creates periods where one style might deliver a higher market premium or expected returns than the other.

Beyond Strict Categories: A Flexible Approach to Investing

While growth investing and value investing are distinct philosophies, many highly successful investors and fund managers adopt a more nuanced and adaptive approach. This perspective suggests that rigidly adhering to one style can limit opportunities or expose an investment portfolio to unnecessary risks during specific market cycles. This is particularly relevant in the context of Modern Portfolio Theory, which emphasizes diversification across different asset classes and investment factors, and considerations for style and size.

This blended approach recognizes that a truly great investment might combine attributes from both camps. For example, a “Growth at a Reasonable Price” (GARP) strategy seeks companies with strong growth prospects that are not excessively expensive. This approach often looks for a PEG ratio (P/E ratio divided by expected earnings growth) near or below 1, indicating reasonable value for the growth offered. It acknowledges that even a fast-growing company should not be bought at any price, while a deeply undervalued company might still lack the growth catalysts needed for significant appreciation.

This strategy emphasizes that all investing, at its heart, is about seeking value for money, whether that value is in current assets or future potential. A rapidly expanding technology company that becomes profitable earlier than expected and starts trading at more reasonable valuations could transition from a pure growth play to a GARP opportunity. Conversely, a stable value company might introduce a new product line or undergo leadership changes that ignite a period of unexpected growth. The market itself is dynamic; companies’ characteristics can change, and the most effective investment strategy often adapts to these realities. This approach prioritizes adaptability and a holistic view of a company’s potential, rather than strict stylistic categorization, making it a form of active investing. Firms like T. Rowe Price offer a range of mutual funds and ETFs that cater to various blends of growth and value investing.

Frequently Asked Questions About Growth vs. Value Investing

Q1: Who are some famous proponents of each style?

A1: Growth Investing: Notable figures include Philip Fisher, who emphasized qualitative factors and long-term potential, and Cathie Wood of ARK Invest, known for her focus on disruptive innovation.

Value Investing: The most famous is Benjamin Graham, considered the “father of value investing”, whose student, Warren Buffett of Berkshire Hathaway, built an empire on its principles.

Q2: Which style performs better over time?

A2: There is no single answer that holds true for all market conditions. The performance of growth vs. value investing tends to be cyclical. Over the past decade and more recently through 2025, growth stocks have generally outperformed, largely driven by the strong performance of big technology companies and areas like artificial intelligence. Historically, value stocks have seen periods of dominance, particularly during economic downturns, times of rising inflation, or when interest rates increase, as reflected in the Russell 1000 Value Index or the S&P 500 Value Index. While growth has led for an extended period, market leadership can rotate. Both styles have experienced periods of significant advantage, and the average premium for one over the other can shift over long timeframes, as confirmed by academic studies and market data.

Q3: Can I have both growth and value stocks in my portfolio?

A3: Yes, absolutely. Many investors create a diversified investment portfolio by holding a mix of both growth stocks and value stocks. This approach aims to capture potential upside from high-growth companies while benefiting from the stability and income of undervalued, mature businesses. This is a common portfolio construction and asset allocation strategy, often implemented through mutual funds or ETFs categorized by fund categories.

Q4: How do market conditions affect these styles?

A4: Rising interest rates typically make future earnings (a key component of growth stock valuations) less attractive, often hurting growth stocks as their discounted future value decreases. Low interest rates tend to favor growth stocks. Economic slowdowns or market downturns can make the stability and dividends of value stocks more appealing. Strong economic booms might see growth stocks soar as future potential looks bright, driven by market sentiment and a focus on capital appreciation.

Q5: How do I identify a growth stock versus a value stock?

A5: Growth Stocks often have: high P/E ratios, high price-to-sales ratios, low or no dividends, and rapid revenue growth. Investors are looking for strong future EPS. Value Stocks often have: low P/E ratios, low price-to-book ratios, high dividend yields, and stable but slower growth. It is important to look at financial fundamentals, financial metrics, and industry trends to make an informed investment decision, focusing on a strong balance sheet and cash flow.

Q6: What are “value traps”?

A6: A “value trap” occurs when a valuation stock appears to be cheap based on its low financial metrics, but its low share price is actually justified by underlying fundamental problems with the business, industry, or competitive landscape. Instead of recovering, the stock continues to decline or stagnate, “trapping” the value investors who bought it. Avoiding these requires thorough due diligence and understanding market behavior. This also includes identifying potential issues with company management or leadership changes.

Concluding Thoughts: Crafting Your Investment Path

Understanding what is growth vs. value investing provides a foundational framework for approaching the stock market. These two powerful investment strategies represent distinct lenses through which to view companies and opportunities. While growth investors chase the excitement of future expansion and innovation, value investors patiently seek out present bargains and a margin of safety. Both approaches have proven merit and generated significant returns for their champions across different economic cycles.

Key Takeaways:

- Growth investing focuses on companies with high future earnings potential, driven by innovation, often trading at higher valuations.

- Value investing seeks companies trading below their intrinsic worth, typically established businesses with strong fundamentals and lower valuation multiples.

- The performance of growth and value stocks is cyclical, influenced significantly by interest rates and broader market dynamics.

- Many successful investors adopt a blended approach, such as “Growth at a Reasonable Price (GARP)” to adapt to changing market conditions.

- Understanding these distinct investment philosophies is crucial for effective portfolio construction and managing investment risk.

- Both strategies require thorough fundamental analysis, but they prioritize different financial metrics and qualitative factors in their investment decisions.