Futures trading involves buying and selling standardized contracts that set the price of an asset for a future date. These contracts trade on regulated exchanges and cover everything from crude oil and wheat to stock indices, interest rates, and currencies.

Futures exist because real-world businesses and investors need a way to manage uncertainty. Producers use futures to lock in selling prices, buyers use them to secure future costs, and traders use them to express a view on where prices are headed. In practice, futures markets help translate expectations about supply, demand, and risk into real-time prices that influence the global economy.

This guide explains what futures trading is, how futures contracts work, what assets can be traded, and the key risks and terms you need to understand before placing a trade.

Key Takeaways on Futures Trading

- Futures trading involves standardized contracts that lock in the price of an asset for a future date.

- Futures markets serve two primary purposes: hedging price risk for businesses and enabling speculation by traders.

- A wide range of assets trade as futures, including commodities, stock indices, interest rates, currencies, and cryptocurrencies.

- Futures use margin and daily settlement, which allows capital efficiency but also requires disciplined risk management.

What Is Futures Trading?

At its heart, a futures contract is a standardized, legally binding agreement to buy or sell a particular commodity or financial instrument at a predetermined price on a specified date in the future.

These contracts are traded on specialized futures exchanges, such as the CME Group (which includes the Chicago Board of Trade) or the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE). Each contract is a standardized asset, defined by the exchange’s specifications and represented by a unique futures symbol.

Key characteristics of futures contracts include:

- Standardization: Each futures contract for a specific asset on a given exchange is identical. It outlines the asset’s quality, quantity, expiration date, delivery procedure (if physical delivery is involved), and minimum price fluctuation (tick size). This uniformity enables active trading and simplifies risk management without requiring negotiation of individual terms.

- Exchange Traded: Futures contracts are bought and sold on regulated exchanges, unlike over-the-counter (OTC) agreements. This ensures transparency, central clearing, and standardized pricing. Market participants can view real-time prices, bid/ask spreads, and order book depth, supporting fair and efficient markets.

- Obligation: Both the buyer (long position) and the seller (short position) are legally obligated to fulfill the contract at expiration. The buyer must purchase and the seller must deliver or settle the asset at the agreed futures price, unless the position is offset before expiry through a closing trade.

- Margin: Instead of paying the full contract value upfront, traders post an initial margin, essentially a good-faith deposit, with a Futures Commission Merchant (FCM). As market prices move, margin accounts are adjusted daily to meet maintenance requirements. While this system allows for leverage and capital efficiency, interest on margin balances is not guaranteed and depends on broker terms.

- Daily Settlement (Mark-to-Market): All open positions are marked to market at the end of each trading day. Gains and losses are credited or debited based on that day’s settlement price, reducing the accumulation of risk over time. This daily reconciliation helps ensure financial stability and reduces the likelihood of default by either party.

Most futures contracts are closed prior to expiration, allowing traders to avoid physical delivery or final cash settlement and instead realize gains or losses through offsetting trades.

Why Do Futures Markets Exist?

Futures markets exist to help participants manage price uncertainty and transfer risk efficiently. They serve two primary functions in the global financial system.

Hedging (Risk Management)

Hedging is the original purpose of futures trading. Businesses and investors use futures contracts to lock in prices and reduce exposure to adverse market movements.

- Producers use futures to secure selling prices for goods they will deliver in the future.

- Consumers and businesses use futures to lock in future purchase costs and stabilize expenses.

- Investors and institutions use futures to hedge portfolio risk without selling underlying assets.

By fixing prices in advance, futures allow market participants to plan with greater certainty.

Speculation (Price Discovery and Liquidity)

Speculators use futures to profit from anticipated price movements in underlying assets.

- Traders buy futures when they expect prices to rise.

- Traders sell futures when they expect prices to fall.

Speculation adds liquidity to futures markets, making it easier for hedgers to enter and exit positions efficiently. This activity also contributes to price discovery by reflecting collective market expectations. active markets to efficiently enter and exit positions. Without speculators, it would be significantly more difficult for hedgers to transfer their price risk.

What Can Be Traded as Futures?

The range of assets that can be traded via futures contracts is incredibly diverse. These instruments span multiple sectors and fall into several key categories:

- Commodity Futures: These represent the oldest and most traditional category of futures contracts, tied to physical goods.

- Agricultural Commodities: Futures are available for products such as corn, wheat, soybeans, coffee, sugar, cotton, cattle, and hogs. These are essential tools for farmers, producers, and agribusinesses to manage seasonal price volatility.

- Energy Commodities: Contracts for crude oil, natural gas, gasoline, and heating oil enable energy producers and consumers to hedge against shifts in global energy prices.

- Metals: Gold, silver, copper, and platinum futures are commonly used by industrial buyers, miners, and investors seeking exposure to precious and industrial metals.

- Financial Futures: These contracts are based on financial instruments or indices and are widely used by institutional investors, corporations, and traders.

- Interest Rate Futures: These include contracts tied to short-term rates (such as Eurodollar futures) and long-term instruments like U.S. Treasury bonds. They are essential for managing interest rate risk across portfolios, including exposure related to Interest Rate Swaps or Mortgage-Backed Securities.

- Currency Futures: These contracts allow participants to lock in exchange rates between currencies. They are commonly used by multinational corporations, import/export businesses, and FX traders to hedge foreign exchange risk.

- Stock Index Futures: Based on indices like the S&P 500 or Dow Jones Industrial Average, these contracts let investors gain or hedge exposure to broad equity markets without trading individual stocks. E-mini futures provide a smaller, more accessible alternative for the same indices.

- Individual Stock Futures: Though less common, some exchanges list futures contracts on single stocks, allowing directional bets or hedges on specific companies.

- Cryptocurrency Futures: A newer addition to regulated markets, futures on digital assets like Bitcoin and Ethereum are now offered on exchanges such as CME Group. These contracts allow traders to speculate or hedge without directly holding the underlying cryptocurrency and are typically cash-settled.

To increase accessibility, many exchanges offer micro futures contracts, which represent a fraction of the notional value of a standard contract. Micro futures on indices, metals, and even cryptocurrencies allow retail traders and smaller investors to participate in the futures markets with lower capital requirements.

Risks and Complexities of Futures Trading

Futures markets play a critical role in modern finance, offering essential tools for hedging and speculation. However, alongside their benefits come several complexities and well-founded criticisms. Many of the features that make futures attractive also introduce significant challenges, particularly for individual investors.

One of the core complexities is leverage, which is built into futures trading through the margin system. Unlike traditional stock investing, where investors typically fund most or all of their positions, futures traders are only required to deposit a small percentage of the contract’s total value as initial margin. For example, while a stock trade might require 50 percent margin, a futures contract often requires just 5 to 10 percent. This means a trader can control a large position with a relatively small capital outlay. While this leverage amplifies potential profits, it also significantly increases the risk of large and rapid losses. For traders unfamiliar with this dynamic, the results can be severe and unexpected.

Another key challenge is the speed and intensity of the futures markets. Futures positions are marked to market daily, meaning profits and losses are settled at the end of each trading day. Traders must ensure that their account balances remain above the maintenance margin requirement. Falling below this level triggers a margin call, which requires immediate additional funding. If the trader cannot meet this requirement, the position may be forcibly closed by the broker. This fast-moving environment demands constant attention, quick decision-making, and robust risk management. It is generally better suited to experienced professionals and institutions rather than to novice investors, who may lack the time, tools, or discipline required. Although tools like stop orders can offer some protection, they do not guarantee execution at desired prices, especially during volatile market conditions.

Additional concerns are raised about the influence of large speculators and algorithmic trading. These participants can increase market liquidity, but they can also contribute to sharp price swings and short-term volatility. In some cases, speculative activity can push futures prices away from the underlying fundamentals of the asset. This disconnection may lead to confusion and added risk for participants trying to hedge or invest based on real-world supply and demand. Complex pricing behaviors, such as convexity bias in interest rate derivatives, further increase the difficulty of accurately evaluating certain contracts.

While futures are a powerful and necessary component of the financial system, they are not without risks. Success in these markets requires a clear understanding of their structure, strict discipline, and a well-developed approach to managing exposure.

Key Futures Trading Terms

Engaging in futures trading requires a solid grasp of key concepts and industry terminology. Below is a structured overview of essential terms and components that every trader should understand before managing a futures account:

Core Futures Trading Terms

- Futures Quote: A real-time display of the current market activity for a specific futures contract. It typically includes the last traded price, bid and ask prices, volume, and open interest. Quotes are essential for monitoring market trends and making trading decisions.

- Futures Symbols: Unique ticker codes that identify specific futures contracts. For example:

- CL represents Crude Oil futures (NYMEX)

- ES represents E-mini S&P 500 futures (CME)

Symbols are often followed by codes for contract month and year (e.g., CLZ5 for December 2025 crude oil).

- Tick Size: The smallest possible price movement for a futures contract. Each contract has a defined tick size and tick value. For instance, crude oil futures (CL) have a tick size of $0.01 per barrel, which equals $10 per contract (since one contract represents 1,000 barrels).

- Notional Value: The total value of the underlying asset that a single futures contract represents. This is calculated by multiplying the current futures price by the contract size. Traders control this full notional amount even though they only post a fraction of it as margin.

Margins and Account Requirements for Futures Trading

- Initial Margin: The minimum amount of capital required to open a new futures position. This is set by the exchange and adjusted by the broker depending on risk and market conditions.

- Maintenance Margin: The minimum balance that must be maintained in the trading account to keep a position open. If the account falls below this level due to market losses, the trader will receive a margin call and must deposit additional funds to restore the balance.

- Mark-to-Market (Daily Settlement): At the end of each trading day, all open futures positions are revalued based on the settlement price. Gains and losses are credited or debited from the trader’s account accordingly. This ensures continuous risk management and transparency.

Settlement Types of Futures Trading

- Cash Settlement: Some futures contracts, particularly financial contracts like equity indices or interest rate futures, settle in cash. Upon expiration, the difference between the entry price and the final settlement price is settled in cash, and no physical delivery occurs.

- Physical Delivery: Less common among retail traders, some futures (such as those for agricultural commodities or energy products) require actual delivery of the underlying asset if the position is held through expiration. Most participants close or roll over positions before delivery occurs.

Related Instruments and Entities

- Futures Options: Derivatives that give the holder the right, but not the obligation to buy (call) or sell (put) a specific futures contract at a predetermined price before or on the expiration date. These are distinct from options on stocks and add another strategic layer for managing futures exposure.

- Futures Commission Merchant (FCM): A registered entity that accepts customer orders to buy or sell futures contracts and holds customer funds in segregated accounts. FCMs are regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC).

- Introducing Broker (IB): A broker that solicits or accepts orders but does not handle customer funds directly. IBs introduce clients to an FCM, who manages the execution and custody of funds.

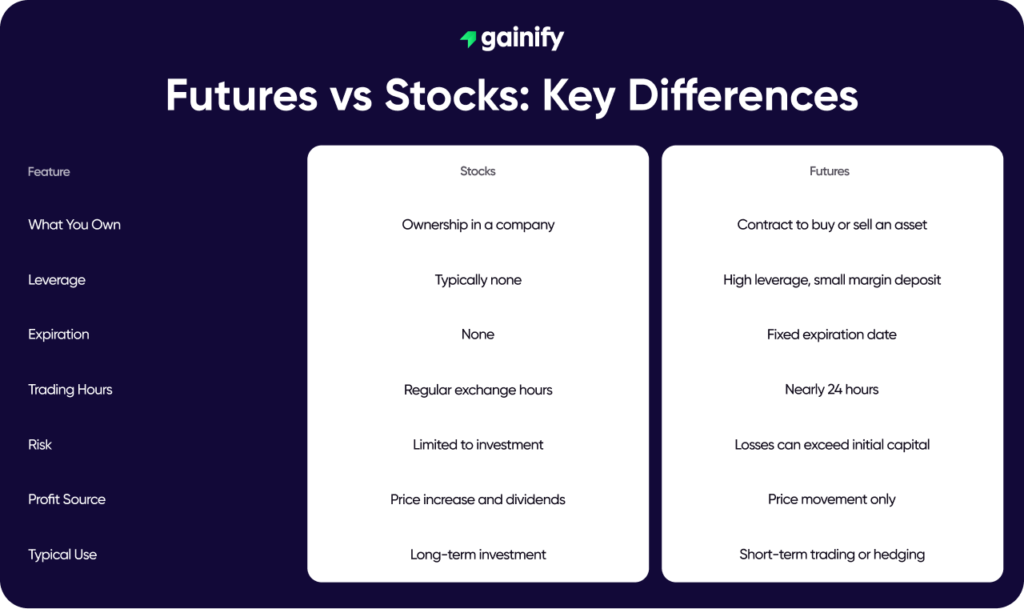

Futures vs. Stocks vs. Options: Key Differences

While futures, stocks, and options are all widely traded instruments, they differ significantly in structure, risk, and use cases.

Feature | Futures | Stocks | Options |

|---|---|---|---|

Underlying exposure | Contract on an asset or index | Ownership in a company | Contract on a stock, index, or future |

Ownership | No ownership of the asset | Shareholder ownership | No ownership unless exercised |

Leverage | High (margin-based) | Low to none | Moderate to high |

Expiration | Yes (fixed date) | No expiration | Yes (fixed date) |

Settlement | Daily mark-to-market | No daily settlement | At expiration or exercise |

Risk profile | High, can exceed initial margin | Limited to investment | Limited to premium paid (buyer) |

Typical users | Hedgers, active traders, institutions | Long-term investors | Traders and hedgers |

The Bottom Line on Futures Trading

Futures trading involves standardized contracts that allow market participants to buy or sell assets at predetermined prices for future delivery. These contracts play a critical role in global markets by enabling businesses to hedge price risk and allowing traders to speculate on price movements across commodities, financial instruments, and indices.

While futures offer capital efficiency through margin and deep market liquidity, they also involve significant risk due to leverage and daily settlement requirements. Successful participation requires a clear understanding of contract mechanics, disciplined risk management, and familiarity with market structure.

For experienced traders, institutions, and businesses managing price exposure, futures trading remains a powerful and essential financial tool. For newer participants, understanding how futures work is a necessary first step before engaging with these markets.

Key Takeaways:

- Futures contracts are standardized agreements for future transactions, used primarily for hedging and speculation.

- They involve significant leverage and daily settlement of profits or losses.

- While offering capital efficiency, futures trading carries high risk and is generally not for beginners.

- The market is regulated, with the CFTC overseeing exchanges like CME Group.

- Most futures contracts are cash-settled, avoiding physical delivery.