If you’re new to investing and studying stocks and businesses, you have probably come across the term value investing quite often.

So, what is value investing?

It’s an approach that encourages investors to evaluate businesses underlying fundamentals (free cash flow, returns on invested capital, balance sheet strength, and durable competitive advantages) to determine a stock’s value, rather than buying a stock based on short-term market sentiment or crowd-driven moves.

Value investing focuses on determining what a company is truly worth and then buying its stock only when the market price falls meaningfully below that estimate.

Let’s explore this approach in detail, how it developed into one of the most influential investment philosophies, and why it still shapes modern thinking on investments.

What Is Value Investing?

Value investing is the practice of buying stocks that are priced below their intrinsic value. This intrinsic value is derived from a company’s economic fundamentals, not from short-term swings in sentiment or headlines.

According to value investors, stock prices often fluctuate because the market misprices businesses in the short run, reacting too strongly to unexpected news or temporary uncertainty. These periods of market overreaction can create opportunities to purchase high-quality companies at significant discounts to their long-term worth.

Rather than chasing momentum, value investors focus on situations where the fundamentals remain intact but the market price disconnects from underlying reality.

A clear illustration of this dynamic occurred during the 2008 financial crisis, when the prices of many fundamentally strong businesses fell sharply .Companies with durable models like Amazon (AMZN), Microsoft (MSFT), and Alphabet (GOOGL) experienced sudden double-digit declines when markets panicked at the onset of COVID. Yet their underlying competitive advantages, cash generation, and long-term earnings power were unchanged or even strengthened.

Investors who purchased during this period of deep undervaluation and held through the recovery were ultimately rewarded as prices realigned with intrinsic value.

History of Value Investing

The concept of value investing traces back to the 1930s, when Benjamin Graham and David Dodd, professors at Columbia Business School, co-authored Security Analysis, a landmark text that formalized the idea of determining a security’s intrinsic value through rigorous, fundamentals-based research. Their framework separated a company’s true economic worth from its often volatile market price.

This philosophy was later advanced by Graham’s most famous student, Warren Buffett, who refined the method into a more business-focused approach. At Berkshire Hathaway, Buffett built a legendary long-term track record by emphasizing quality companies, durable competitive advantages, and disciplined valuation. His application of value principles helped make him one of the most successful investors in history.

Beyond Buffett, many other renowned investors have drawn from Graham and Dodd’s work, including Walter Schloss, Seth Klarman, and Charlie Munger. Each applied the core idea of buying undervalued businesses while adapting it to their own style, whether through deep value, quality value, or opportunistic contrarian strategies. Despite variations, the central principle remains the same: use independent fundamental analysis to buy companies for less than their intrinsic value.

How Value Investing Works

Value investing is built on a simple principle: if you understand a company’s true economic value, you can make informed decisions about whether its stock is cheap or expensive. While intrinsic value typically changes slowly, stock prices can swing sharply due to short-term sentiment, temporary uncertainty, or market overreaction. These mismatches between price and value create opportunities for disciplined investors.

To evaluate whether a stock is genuinely undervalued, investors examine several core financial and competitive factors that shape long-term business performance.

Understanding Intrinsic Value

Intrinsic value represents the underlying worth of a company, based on fundamentals such as cash flow generation, earnings power, asset quality, return on invested capital, and competitive durability.

It deliberately excludes short-term factors like market price, investor emotions, or recent headlines.

Value investors assess intrinsic value by analyzing:

- Financial fundamentals, including revenue quality, profit margins, free cash flow, balance sheet strength, and long-term profitability.

- Economic fundamentals, such as brand strength, market position, pricing power, industry structure, and the defensibility of the business model.

Together, these elements form a holistic view of what the business is worth, independent of market fluctuations.

Margin of Safety

Margin of Safety is the gap between a stock’s intrinsic value and its current market price.

Purchasing a stock priced within the margin of safety (MOS) allows investors to buy at a price significantly below the stock’s true worth. This way, they are protected against market volatility, unforeseen issues in their business, and human errors.

Ultimately, staying within the margin of safety when buying stocks provides a cushion against downside risks and better potential for profits.

Here’s how this is calculated:

MOS%= ((Intrinsic Value – Market Price)/ Intrinsic Value)*100%

Key Metrics and Ratios for Value Investing

The most important metrics that help value investors conduct a company’s fundamental analysis include:

- Free Cash Flow: The cash obtained from the revenue or operations of the company after deducting the costs of all expenditures.

- Price-to-Earnings-to-Growth (PEG) ratio: This ratio measures how expensive a stock is relative to its expected growth rate.

- Price-to-earnings (P/E ratio): The ratio of the stock price to the earnings per share. It determines if the stock is undervalued or if the stock price is not reflecting the company’s earnings.

- Price-to-book (P/B ratio): The ratio of the market price of a share to the value of the company’s assets. In case the price is lower than the asset value, the stock would be undervalued, and vice versa.

Using these metrics, it’s easy to determine if a stock is currently priced below its true worth.

Types of Value Investing Strategies

Value investors use different approaches depending on how they identify undervaluation, the quality of the underlying business, and their risk tolerance. While the core principle is the same, these strategies vary in how aggressively they pursue mispriced stocks.

Here are the four most common value investing styles:

- Relative Value Investing: Investors compare a company’s valuation to peers, its own historical multiples, and the broader market. The goal is to find stocks that trade at a discount relative to comparable businesses, under the expectation that valuation gaps eventually normalize.

- Deep Value Investing: Focuses on companies that are trading at substantial discounts to quantitative measures, such as Net Asset Value or liquidation value. These stocks often look extremely cheap on metrics like P/B or EV/EBITDA, and the thesis relies on the market eventually recognizing that the discount is too severe.

- Quality Value Investing: A modern approach centered on buying high-quality companies at reasonable or discounted prices. These businesses typically have strong competitive advantages, consistent profitability, high returns on capital, and capable management. The strategy seeks value not just in price, but in the long-term durability of the business.

- Contrarian investing: This strategy deliberately moves against prevailing market sentiment. Investors target companies that are temporarily distressed or out of favor, assuming that the decline in price is due to market overreaction rather than permanent deterioration. It requires patience and a strong understanding of why sentiment will eventually shift.

Industries and Sectors for Value Investing

Value investors search for companies with strong balance sheets, relatively low price-to-earnings ratios, and a stable potential for earnings. Here are the leading sectors for value investing:

- Utilities and Energy: Energy companies frequently trade at low valuation multiples despite generating substantial free cash flow, especially when commodity prices are supportive. Cyclical downturns often create temporary mispricing, allowing investors to buy durable producers at discounts.

- Banking and Financials: Banks and financial institutions can offer value opportunities when asset quality improves, credit costs normalize, or interest rate conditions become favorable. These firms often trade at discounts to book value during periods of uncertainty.

- Infrastructure: Infrastructure businesses benefit from long-term government spending, regulated frameworks, and predictable demand. Their revenue stability and long-duration cash flows make them attractive for value-focused investors seeking resilient returns.

- Mining and Metals: This sector tends to be highly cyclical. Stocks may trade at depressed valuations during downturns, despite owning valuable natural resources. When economic conditions improve, earnings can recover sharply, creating significant upside.

- Consumer Staples: Companies that sell essential goods benefit from consistent demand, strong brand loyalty, and defensive characteristics. Their earnings stability often reveals value when the sector temporarily falls out of favor.

How to Identify Value Stocks

While you must understand value investing in theory, it’s equally important to follow a practical step-by-step method to apply the model in real time:

Step 1: The Screening

The process should start by narrowing down to the stocks that meet basic value criteria.

- Investors can consider stocks with a P/E Ratio between 0 and 15

- A P/B Ratio less than 1.5

- Market capitalization of greater than $1 billion

- Debt-to-Equity ratio less than 1.0

Step 2: The Research

For each of the undervalued stocks that investors consider, they need to study:

- The company’s business model

- Whether the Management Team is experienced

- Whether the Team is friendly to shareholders

- The company’s competitive advantage

Step 3: The Calculation

Once you’re done with the company research, you need to calculate the essential metrics for stock valuation to understand the ideal margin of safety:

- For each stock, find the P/B and P/E ratios relative to the industry

- After the stock’s intrinsic value is estimated, it should be compared to the current price

- A significant margin between the two makes value investors more confident in an investment decision

Step 4: The Decision-Making

If a company meets an investor’s criteria, is financially sound in terms of vital metrics, has a strong business, and is offering a discounted stock price, it can go ahead and make the purchase.

That said, even after buying a stock, investors should carefully track its performance. Successful value investing often requires holding a stock for months or years, even if its true value isn’t immediately reflected in the market.

Value Investing vs. Growth Investing

Criteria | Value Investing | Growth Investing |

Earnings | Low P/E values | High growth in earnings |

Price | Undervalued stocks, priced lower than the market | Overvalued stocks are priced higher than the broader market |

Low or no yields from Dividends | ||

Risk | More stable with low stock volatility | High risk with relatively higher stock volatility |

Benefits and Advantages of Value Investing

- Potential for high returns.Buying stocks at a meaningful discount to intrinsic value allows investors to benefit when the market eventually corrects the mispricing. As the gap between price and value closes, returns can compound significantly.

- Mitigated risk. When a stock is purchased below its true worth, the margin of safety helps protect investors from losses even if future results fall short of expectations. Undervalued companies have a lower bar to clear for the investment to be successful.

- Focus on solid businesses. Value investing naturally directs attention toward companies with proven financial resilience, durable business models, and stable cash flows. This emphasis on quality helps investors avoid speculative or overly volatile stocks.

Risks and Limitations of Value Investing

- Misjudging intrinsic value. Value investing depends on accurate analysis. If investors misestimate earnings power, cash flow durability, or competitive risk, they may conclude that a stock is cheap when it is not. A flawed valuation model can turn a perceived bargain into a value trap.

- Relying on outdated or incomplete information. Intrinsic value changes over time. Using stale financial statements, ignoring recent guidance, or overlooking structural shifts can lead to poor decisions. High-quality value investing requires continuous monitoring and updated data.

- Confusing temporary problems with permanent impairment. Some businesses face short-lived setbacks, while others suffer from structural decline. Mistaking the latter for the former is one of the most common value-investing errors. Cheap stocks often look cheap for a reason.

- Overpaying or buying too close to fair value. The margin of safety only exists if the purchase price is meaningfully below intrinsic value. Investors who buy too close to fair value lose that buffer and take on asymmetric downside risk.

- Overreliance on financial ratios. Single metrics like P/E or P/B can be misleading without context. Accounting differences, industry norms, and one-time events distort ratios. Skilled investors cross-check multiple valuation measures and pair quantitative analysis with qualitative judgment.

- Patience required, but not guaranteed. Value trades can take months or years to play out, testing investor discipline. Some undervaluations correct quickly, others never do. Market sentiment can remain irrational long enough to frustrate even experienced investors.

Famous Value Investors and Success Stories

Several top investors across generations have adopted value investment strategies to earn double-digit returns for years, and sometimes decades. Here is a brief insight into two noteworthy personalities among them and their achievements:

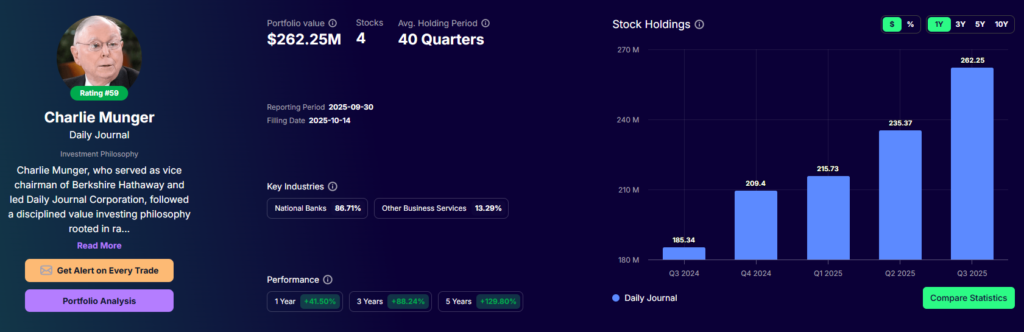

- Charlie Munger

Munger is Warren Buffett’s long-term business partner and Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway. Starting out as a lawyer in California, he transitioned to investment and finance and had a successful investing career of his own before joining Berkshire.

His emphasis was on “buying a wonderful company” with excellent management and strong “moats” at a fair price rather than a “fair company” at a “wonderful price”.

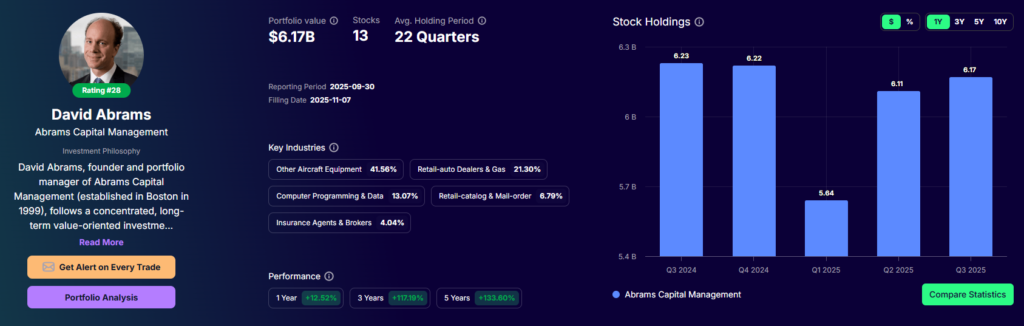

- David Abrams

Abrams has quietly built a hedge fund managing just under $10 billion in assets, relying on minimal marketing or fundraising.

As founder and head of Boston-based Abrams Capital Management since 1999, he delivered an annualized net return of 15% for investors over the fund’s first 15 years. The fund is unlevered, holding significant cash reserves rather than borrowing to amplify returns.

Abrams Capital runs a highly concentrated portfolio. An August 2024 SEC Form 13-F filing shows the fund’s largest positions included Loar Holdings, Lithia Motors, Asbury Automotive Group, Alphabet, and Meta.

Conclusion

Understanding what value investing is highlights the importance of buying high-quality businesses at prices that offer meaningful value, rather than following short-term market trends.

This approach relies on rigorous research, independent judgment, and patience, not reaction to daily volatility. Markets evolve, sentiment shifts, and cycles come and go, but the core principles of value investing remain durable because they are grounded in economic reality, not speculation.

By applying sound valuation methods, maintaining a margin of safety, and continually reassessing a company’s fundamentals, investors can build portfolios that are more resilient, more disciplined, and better positioned for long-term wealth creation.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Is value investing still relevant today?

Yes, focusing on margin of safety and intrinsic value can still work, but it may yield cyclical returns relative to growth styles, depending on the market environment.

- How much money do I need to start value investing?

Investors generally start with fractional shares or very small amounts, with prices as low as $10. What matters in this approach is regular diversification and investing.

- What is the difference between value investing and dividend investing?

Value investing targets underpriced businesses based on fundamentals, while dividend investing focuses on shares that pay attractive, reliable cash payouts.

- Can value investing work in growth sectors like technology?

Yes, you can apply the principles of value investing to technology by valuing moats, cash flows, and realistic growth rather than market sentiment or hype.

- How long does it take to see returns from value investing?

Investors can expect to see results over 3-5 years, since mispriced stocks take time to regain their market value.

- What are the most common value traps to avoid?

Avoid “cheap” stocks with features such as declining industry prospects, shrinking market share, high debt, opaque accounting, and weak cash flows.

- Is value investing better than growth investing?

Neither strategy can be called superior to the other. While value investing focuses on undervalued fundamentals, growth investing considers rapid company expansion as a primary criterion for selecting stocks.

- How do I calculate a company’s intrinsic value?

Most investors estimate intrinsic value using discounted cash flow (DCF) models and then cross-check it against ratios like P/E, P/B, and EV/EBITDA relative to the company’s peers.

- What books should I read to learn value investing?

The best books to start with are The Intelligent Investor, Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits, and Security Analysis.

- Can I use value investing for retirement planning?

Yes, once you own a diversified portfolio of fairly valued, quality, or undervalued stocks, you can support retirement income and long-term wealth building.