One of the most common questions on a red day is “why are stocks down today?”

There is rarely a single explanation. Markets can fall because of macroeconomic shifts, company-specific disappointments, or changes in investor sentiment. Sometimes the move is triggered by data releases. Other times it is driven by technical factors that snowball once fear takes hold.

In practice, several themes typically explain why equities lose ground:

❌ Rising Treasury yields. When bond returns move higher, stocks become less attractive in comparison.

❌ Employment data or inflation data. Signs of slowing growth or persistent price pressures weigh on sentiment.

❌ Central bank signals at an FOMC meeting. Markets react when policymakers indicate that financial conditions will remain tight.

❌ Geopolitical tensions. Uncertainty pushes investors toward safe assets such as gold or Treasuries.

❌ Earnings misses. Disappointing results or weaker guidance from large companies drag indexes lower.

❌ High valuations. Expensive stocks leave little room for error and are vulnerable to corrections.

❌ Technical selling. Fear-driven moves, often reflected in a rising Cboe Volatility Index®, accelerate declines.

Each of these factors can push stocks down on its own. When several appear at the same time, the pressure on markets intensifies and losses can feel sharper.

Typically these reasons fall into two categories. Understanding why stocks are falling today requires looking at both broader market dynamics and idiosyncratic stock-specific factors.

Broader Market Reasons

Rising Treasury Yields

Bond yields remain one of the most influential forces shaping equity markets. When the Treasury yield on government securities rises meaningfully or moves sharply in a short period, equities typically lose some of their relative appeal. Investors tend to pay closer attention to these shifts during periods of heightened volatility, since yield moves can alter risk appetite across asset classes.

There are two main channels through which yields affect equities:

- Relative Attractiveness

A 10-year Treasury yielding 5 percent offers what is often considered a near risk-free return. In such an environment, the reward for holding equities needs to be considerably higher to justify the additional risk. If that risk premium appears compressed, investors may rotate capital toward bonds. This type of allocation shift can have visible effects on benchmarks such as the S&P 500 Index, the Nasdaq Composite, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average. - Discount Rate Effect

Stock valuations depend heavily on the present value of future earnings. When yields rise, the discount rate increases, which lowers those valuations. The impact is not uniform. Companies whose earnings are projected far into the future, typically high-growth names, including many AI stocks are the most sensitive to such adjustments. This helps explain why the technology sector (especially AI stocks) often leads declines during periods of rapid yield increases.

Weak Economic Data

Markets are forward-looking, which is why they react quickly to signs of slowing momentum. Investors closely monitor economic indicators such as:

- Monthly payroll reports and jobless claims from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- Home sales data as a proxy for consumer confidence and housing demand.

- ISM Manufacturing PMI, which offers an early read on business activity.

- GDP growth releases and revisions.

When these reports fall short of expectations, markets begin to price in weaker revenue and profit growth. Even modest disappointments can have an outsized impact because they influence expectations for future earnings and monetary policy.

Geopolitical Uncertainty

Geopolitical risks, even when distant, can ripple through global capital markets. Investors remain acutely aware that conflicts, sanctions, and disruptions to supply chains affect both trade flows and commodity prices.

Energy shocks are a particularly destabilizing factor. Rising oil prices and spikes in WTI Crude Oil futures increase costs for households and corporations. Margins are compressed, while elevated gasoline prices erode consumer spending power.

Periods of uncertainty often coincide with a flight to safe-haven assets such as gold prices and Treasuries. This retreat away from equities is frequently accompanied by surges in the Cboe Volatility Index®, reflecting heightened investor anxiety.

Central Bank Policy

Central banks continue to set the overall tone for financial markets. Equities are especially sensitive to policy signals that indicate how long interest rates may remain restrictive. When the Federal Reserve’s minutes of meeting or official statements suggest a “higher-for-longer” approach, markets often respond with renewed caution.

The Personal Consumption Expenditures index, one of the Fed’s preferred measures of inflation, remains above target even as headline pressures have moderated. For policymakers, this justifies keeping conditions tighter than investors may prefer. At the most recent FOMC meeting, the Fed delivered its first rate cut of the cycle. The move was largely in line with expectations and therefore did not generate a major surprise for markets. What investors continue to debate is the likely path and pace of future cuts, which remain dependent on incoming data.

For equities, this means monetary policy is shifting toward accommodation, but uncertainty around the broader trajectory of rates still might weigh on valuations and sentiment.

Stock-Specific and Sector-Specific Reasons (Idiosyncratic Factors)

Earnings Misses and Guidance Cuts

Corporate earnings remain the most important anchor for equity valuations. When results come in weaker than consensus expectations, the reaction in share prices is often immediate. What tends to matter even more is forward-looking guidance. If management signals caution about the coming quarters, markets typically adjust not only the company’s valuation but also sentiment across its sector.

Because megacap firms carry such significant weight in major benchmarks, even a small number of earnings disappointments can pull down the broader S&P 500 Index or Nasdaq Composite. This has been especially visible in the technology sector, where investor focus on AI stocks magnifies both upside and downside reactions.

Valuation Concerns

Valuations are ultimately about expectations. When multiples rise to levels that appear stretched relative to earnings power, investors begin to reassess sustainability. High valuations do not guarantee declines, but they increase vulnerability to even modest disappointments.

For example, a company trading at 40 times forward earnings may perform well fundamentally, yet any deceleration in revenue growth or margin pressure can trigger a sharp rerating. This process, known as multiple compression, can reduce equity prices even when absolute profits remain stable.

Sector Rotation

Equity weakness does not always reflect a collapse in fundamentals. It can also result from portfolio reallocations, often described as sector rotation. Institutional investors continuously adjust exposures in response to macro signals, valuations, and relative earnings outlooks.

- When Treasury yields rise, financials may attract flows while long-duration growth sectors like technology see selling pressure.

- In periods of uncertainty around inflation data or GDP growth, defensive groups such as consumer staples and healthcare tend to outperform.

- Higher oil prices and strong WTI Crude Oil trends often channel flows into energy, while rate-sensitive sectors like real estate and utilities underperform.

These rotations can create the impression of broad market weakness, particularly when the sectors being sold have large index weightings.

Technical and Sentiment Factors

Not all market moves are explained by fundamentals. Technical levels and investor psychology play an important role in amplifying volatility.

- Technical triggers. When major benchmarks such as the S&P 500 Index fall below widely followed levels like the 200-day moving average, algorithmic strategies and stop-loss orders can accelerate selling.

- Sentiment dynamics. Fear and uncertainty can drive exits even in the absence of new data. Selling can quickly become self-reinforcing, as investors respond to market moves themselves rather than underlying fundamentals.

Narratives also matter. Media coverage emphasizing risks such as the recent U.S. government shutdown, weaker employment data, or persistent inflation reinforces a cautious mood. Once negative sentiment takes hold, it can shape flows in ways that appear disproportionate to the news itself.

Why Market Moves Look Exaggerated

Equity market declines often appear larger than the underlying news might suggest. This is not only about fundamentals but about how market structure, positioning, and psychology interact in periods of stress. A few common amplifiers include:

- Leverage and forced selling. Many hedge funds and institutional investors employ leverage to enhance returns. When markets fall, margin calls and risk limits can force liquidations at the worst possible moment, creating a feedback loop that accelerates declines.

- Passive investment flows. In an era dominated by ETFs and index funds, outflows can lead to indiscriminate selling. When investors pull money from an S&P 500 Index tracker, every stock in the benchmark is sold regardless of fundamentals, spreading pressure broadly.

- Algorithmic and momentum trading. Systematic strategies often respond to volatility itself rather than underlying economic drivers. Once the Cboe Volatility Index® rises, volatility-targeting funds and hedging programs may scale back equity exposure, reinforcing downward momentum.

- Narrative amplification. Market psychology plays a role too. Headlines emphasizing risks such as a government shutdown, weak home sales, or slowing GDP growth can magnify fear. As narratives take hold, selling can become self-reinforcing even if the data does not materially worsen.

In practice, these dynamics rarely operate in isolation. They interact with each other, turning what might have been a modest adjustment into a sharper move. This helps explain why equity markets sometimes overshoot in both directions, particularly during periods of heightened uncertainty.

How Investors Respond

Investors typically react to market declines in a variety of ways, depending on their strategy and risk appetite:

👉 Flight to safety: Many shift into Treasuries, cash, or gold. The move into gold prices or short-term government paper reflects a defensive instinct when uncertainty rises.

👉 Buying the dip: Contrarians often see volatility as an opportunity. For example, during events like the October 2025 government shutdown, they argue disruptions are temporary and position for a rebound.

👉 Rebalancing: Institutional investors such as pension funds tend to adjust mechanically. If equities fall relative to bonds, they buy stocks to bring portfolios back to target allocations.

👉 Hedging: Managers often turn to derivatives or credit instruments. Options tied to the Cboe Volatility Index or allocations to corporate bonds help manage downside risk.

Together, these behaviors interact to shape market dynamics, with defensive moves sometimes reinforcing volatility and contrarian buying providing stabilizing flows.

Should Investors Worry?

Here the answer is more subtle than a simple yes or no. Pullbacks are a normal feature of equity markets, often acting as a necessary reset for valuations. The challenge lies in assessing whether the drivers are short-term or long-term in nature:

Temporary Drivers | Structural Drivers |

October 2025 government shutdown, which delayed reports such as the monthly payroll report and jobless claims | Persistently high oil prices that weigh on margins and consumer demand |

One-off geopolitical flare-ups that shift sentiment temporarily | Weakening GDP growth that signals sustained economic slowdown |

Delayed data releases or short-lived disruptions | Inflation pressures that keep policy restrictive over multiple quarters |

Key takeaway: Not every decline signals a bear market. Investors should focus less on the fact that stocks are down and more on whether the underlying reasons suggest a temporary adjustment or a structural shift in fundamentals.

Conclusion

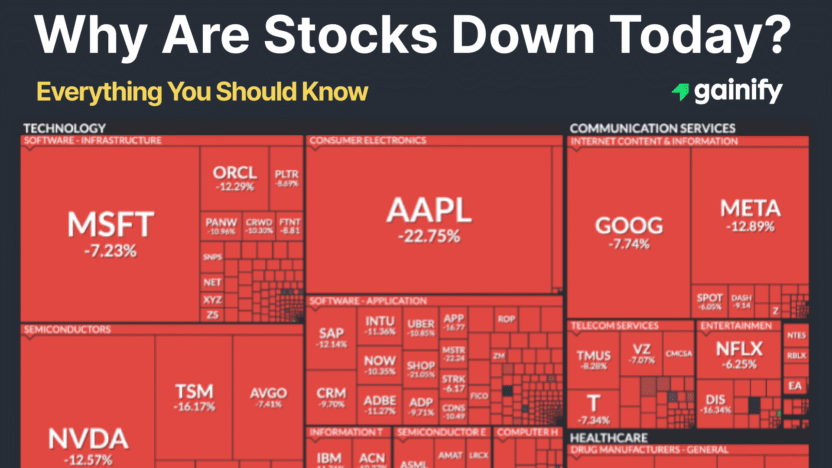

Stocks are down today because systemic forces and company-specific disappointments are aligned against equities. Rising Treasury yields, cautious FOMC meeting minutes, sticky inflation data, geopolitical risks, and uncertainty following the government shutdown all weigh on markets. Meanwhile, disappointing earnings, stretched valuations in AI stocks, sector rotation, and technical triggers amplify the selling.

Major benchmarks including the S&P 500 Index, the Nasdaq Composite, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average reflect these pressures. Safe havens such as gold prices are benefiting, while WTI Crude Oil and higher oil prices compound risks.

History shows that such declines are not unusual. Whether this episode proves temporary or structural will depend on upcoming reports from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, signals from the Fed’s minutes of meeting, and data on GDP growth, home sales, and the Personal Consumption Expenditures index.

For long-term investors, the lesson is clear: volatility is part of the journey, and disciplined stock analysis combined with diversification remains the best way to navigate uncertainty.