A private equity firm is an investment management company that raises capital from institutional and accredited investors to buy ownership stakes in businesses.

These firms invest primarily in private companies or acquire public companies and take them private. Their objective is to improve the performance and value of those businesses over time and eventually sell them at a profit.

Private equity firms have backed everything from tech startups and healthcare providers to restaurant chains and manufacturing giants. As of Jan 2026, U.S. private equity firms managed a record $3.5 trillion in assets.

Private equity firms differ from public market investors because they take an active role in the companies they own. Rather than passively holding shares, they work closely with management teams to improve operations, refine business strategy, and strengthen financial performance.

This article explains what a private equity firm is, how private equity firms are structured, how they generate returns, the strategies they use to create value, and how investors gain access to private equity opportunities.

4 Things You Need to Know About Private Equity Firms

- Private equity firms raise capital through investment funds. These funds are backed by institutional and accredited investors who commit capital for a defined investment period.

- They invest in businesses through equity ownership. Investments typically involve acquiring significant or controlling stakes in private companies or taking public companies private.

- Value creation is an active process. Private equity firms work with management teams to improve operations, strengthen financial performance, and support long-term growth.

- Returns are realized over multi-year timelines. Investments are held for several years, with exits occurring through sales, public offerings, or secondary transactions.

What is a Private Equity Firm?

A private equity firm is an investment management company that raises capital from institutional and accredited investors to acquire ownership stakes in businesses. These firms primarily invest in private companies or take public companies private, with the goal of increasing enterprise value over time.

Private equity firms invest through dedicated funds that have defined lifespans, often spanning seven to ten years. Investors commit capital during a fundraising period, and the firm deploys that capital across multiple portfolio companies.

Ownership in private equity is active in nature. Firms work closely with management teams to improve operations, strengthen financial performance, and refine business strategy as part of a long-term value creation plan.

Because private equity investments are illiquid, capital is typically held for several years. Returns are realized through exit events such as company sales, public offerings, or secondary transactions.

How Private Equity Firms Are Structured

At its simplest, a private equity firm is an investment adviser that raises capital from institutional and accredited investors to acquire equity ownership in companies. Unlike public market investors who buy shares on exchanges, private equity firms typically seek to purchase a controlling interest, or even full ownership, of private companies, or take public companies private. This process is a core part of asset management within the broader capital markets.

The capital managed by a private equity firm primarily comes from:

- Limited Partners (LPs): These are the private equity investors who provide the capital. They include large institutional investors like pension funds, university endowments, insurance companies, and sovereign wealth funds. Their liability is typically limited to the amount of capital they commit.

- General Partners (GPs): This refers to the private equity firm itself, acting as the fund manager. The GPs are responsible for managing the investment fund, identifying deals, conducting due diligence, and overseeing the portfolio companies. They often contribute a small percentage of the fund’s capital.

A key aspect of alignment in private equity is that GPs typically invest a significant amount of their own capital into the funds they manage. Sometimes, LPs will then choose to invest even more capital directly into specific portfolio companies alongside the GP. This co-investment strategy deepens the alignment of interests, demonstrating the GP’s strong conviction in a particular deal, and often allows LPs to gain more focused exposure with reduced fees and expenses on that specific portion of their investment.

These investors commit capital to specific private equity funds, which the firm then uses to make investments over a defined period, often 5 to 10 years. The goal is to generate significant returns for these investors by improving the performance and value of the acquired companies before exiting the investment.

How Private Equity Firms Make Money

The compensation structure for private equity firms is typically based on a “2 and 20” model, though variations exist. This includes two main components:

- Management Fee: This is an annual management fee charged as a percentage of the assets under management (AUM), typically ranging from 1.5% to 2.5%. This fee covers the firm’s operating expenses, salaries for its professionals, and other overheads. These management fees are paid regardless of the fund’s performance. For very large funds, the percentage might be slightly lower.

- Carried Interest (Performance Fee): This is the more significant component and serves as a performance fee. It represents a share of the investment profits generated by the fund, typically 20%. This carried interest is usually only paid to the fund manager after the Limited Partners have received their initial capital back and often a preferred return (a hurdle rate, commonly 7% to 8%). This aligns the interests of the GP with the LPs, incentivizing high performance. If the fund performs exceptionally well, the carried interest can lead to substantial payouts for the firm’s partners.

Beyond these main ways of earning income, private equity firms can also generate revenue from other sources. They might collect transaction fees for their involvement in merger acquisition activities. They can also charge monitoring fees for overseeing their portfolio companies, or earn fees for providing additional advisory services to these businesses. The transparency surrounding all these fees and expenses has become a significant area of focus for financial regulators.

How Private Equity Firms Operate: Key Strategies

Private equity firms employ various investment strategies to acquire and grow companies. They are active managers, not passive investors, deeply involved in transforming the businesses they acquire. Their role is that of a financial sponsor, providing both capital and expertise.

Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs): This is the most common and widely recognized private equity strategy. In an LBO transaction, a private equity firm acquires a company using a significant amount of borrowed money, or leverage. The assets of the acquired company often serve as collateral for these loans. The firm then works to improve the company’s operations, increase its profitability, and reduce debt over several years, before eventually selling it for a profit. The leverage can magnify returns if the company performs well, but it also amplifies losses if it does not. The debt-to-enterprise value ratios in LBOs can be substantial, making the investment sensitive to fluctuations in interest rates.

- A prime example of a successful LBO is Blackstone’s 2007 acquisition of Hilton Hotels. Despite the challenge of the 2008 financial crisis hitting shortly after the deal, Blackstone successfully restructured Hilton’s debt, implemented operational efficiencies, and supported its global expansion. They ultimately exited their stake years later for a significant profit, demonstrating the potential for long-term value creation even from troubled market conditions.

- Another notable success involved BC Partners’ acquisition of PetSmart in 2014. This deal, valued at $8.7 billion, was driven by the pet retailer’s strong cash-flow sources. BC Partners then facilitated PetSmart’s strategic acquisition of Chewy.com, a major online pet retailer, significantly expanding its e-commerce presence and creating substantial value before spinning off Chewy in an IPO.

- For a different kind of success, consider Silver Lake’s 2013 take-private of Dell Technologies (then Dell Inc.). This LBO allowed a publicly listed company to undergo a major restructuring and innovate away from short-term public market pressures, eventually returning parts of the company to the public markets as a stronger entity.

- On the more challenging side, the 2007 buyout of TXU Corp. (now Energy Future Holdings) by a consortium that included TPG and KKR stands out. This highly leveraged $45 billion deal later faced bankruptcy due to its immense debt burden combined with declining natural gas prices and a challenging regulatory environment, resulting in significant losses for investors.

- Another instance of a scrutinized LBO involves the 2011 acquisition of Blue Harvest, a major player in the US fishing industry, by a private equity firm. While the firm aimed to consolidate and modernize the industry, the deal faced ongoing scrutiny regarding its impact on local fishing communities, marine resources, and marine affairs, ultimately encountering technical difficulties and financial struggles. This case highlights the complexities when private equity enters heavily regulated or socially sensitive sectors.

Venture Capital (VC): While often operating as distinct entities, venture capital is a form of private equity focused on investing in early stage, high-growth potential companies that are typically not yet profitable. Venture capitalists provide funding in exchange for equity, aiming for massive returns if a private equity startup becomes highly successful. Iconic early investments in tech giants like Google or Facebook by firms such as Sequoia Capital are classic venture capital successes.

Growth Equity: This strategy involves providing growth capital to more mature, already profitable companies that need funds for major growth initiatives, such as expanding into new markets or developing new products. Unlike LBOs, growth equity deals often use less leverage and the private equity firm may take a significant minority stake rather than full control. For instance, TPG Growth might invest in a software company seeking to expand globally without taking on excessive debt.

Distressed Investments: Some private equity firms specialize in acquiring struggling or financially distressed companies by investing in distressed securities. They aim to turn these businesses around through operational improvements, debt restructuring, and a capital injection. This can be a high-risk, high-reward strategy. An example could be a private equity firm acquiring a retail chain on the verge of bankruptcy, then revamping its supply chain and marketing.

Mezzanine Capital: This involves providing hybrid debt and equity financing. It is a layer of capital that sits between senior debt and equity on a company’s balance sheet, offering higher returns for higher risk. This type of financing might be used to fund a management buyout or a large expansion project.

How Private Equity Firms Create Value

Private equity firms actively enhance the value of their portfolio companies through several key avenues, driving significant cash generation:

- Operational Improvements: This is a major focus. Firms bring in experienced teams to streamline operations, optimize supply chain optimisation, cut inefficient costs, and enhance productivity. They might implement new technologies or refine business processes.

- Strategic Growth: They identify and support new growth initiatives, such as expanding into new markets, introducing new products or services, or pursuing complementary acquisitions (add-ons). They redefine a company’s strategic trajectory.

- Financial Engineering: This involves optimizing the company’s capital structure, often by reducing debt or refinancing it at lower interest rates, to improve financial performance.

- Strong Management and Governance: Private equity firms often replace or strengthen management teams, bringing in experienced leaders who can execute the value creation plan effectively. They typically secure multiple board seats and influence the board of directors to ensure strategic alignment and robust private equity ownership oversight. This often involves implementing strict reporting upgrades.

Leading Private Equity Firms and Their Focus

The private equity industry is characterized by the presence of a few very large, globally active firms that manage vast sums of capital. These firms conduct extensive manager selection to build their teams and execute complex investment strategies. Their sheer size and consistent ability to raise private equity funds underscore their dominant position in the capital markets.

While AUM figures can fluctuate based on market conditions and new fundraising, here are some of the leading private equity firms by their approximate assets under management as of late 2024 or early 2025, encompassing their broader alternative asset platforms where private equity is a core component:

- Blackstone (BX): Consistently the largest alternative asset manager globally, with over $1 trillion in AUM. Blackstone has a monumental presence across private equity, real estate, infrastructure, and credit. Noted transactions include its historic acquisition of Hilton Hotels and more recent investments in critical sectors like logistics, life sciences, and digital infrastructure. Their expertise spans diverse buyouts and a wide array of alternative strategies.

- Apollo Global Management (APO): A formidable force in alternative asset management, managing over $670 billion in AUM. Apollo is known for its opportunistic and value-oriented approach, investing across credit, private equity, and real assets. Their portfolio has included companies like Shutterfly, ADT, and Rackspace Technology, often engaging in complex LBO transaction structures and distressed securities investments.

- KKR (Kohlberg Kravis Roberts): A true pioneer in the leveraged buyout model, managing over $570 billion in AUM. KKR is widely recognized for the historic RJR Nabisco deal. Today, KKR invests across multiple asset classes, including private equity, infrastructure, real estate, and credit. The firm is active in sectors such as consumer, healthcare, and technology, frequently engaging in large-scale merger acquisition activity.

- Carlyle Group (CG): A global investment firm with robust activity across corporate private equity, real assets, and global credit. Carlyle managed more than $425 billion in AUM. Carlyle frequently targets industries such as aerospace, defense, healthcare, and industrials, focusing on operational improvements and value creation for its private equity-backed firms.

- Ares Management (ARES): While strong in credit, Ares has a significant private equity presence, managing over $430 billion in AUM across its various strategies. The firm is known for its flexible capital solutions and strategic investments in areas like healthcare, power, and infrastructure.

- Brookfield Asset Management (BAM): While a broader alternative asset manager with nearly $1 trillion in AUM overall, Brookfield has a substantial private equity platform. They specialize in real assets, infrastructure, and renewable power, often taking large stakes in fundamental service companies globally.

- TPG: Founded by David Bonderman and Jim Coulter, TPG manages a diverse portfolio with approximately $225 billion in AUM. The firm has strong interests in technology, healthcare, and consumer businesses. It has invested in companies such as Chobani and Airbnb, and was part of the Burger King acquisition consortium alongside Bain Capital and Goldman Sachs.

- Thoma Bravo: A leading firm highly specialized in software and enterprise technology investments, managing over $138 billion in AUM. Thoma Bravo is renowned for its consistent focus on operational efficiency and long-term growth across its portfolio, which includes companies like Proofpoint, SailPoint, and Coupa Software. It is considered one of the most active private equity firms in the software sector globally.

- Vista Equity Partners: Another firm with a dedicated focus on software, data, and technology-enabled organizations. Vista manages substantial AUM, consistently deploying capital into high-growth software companies and driving significant operational improvements.

- CVC Capital Partners: A prominent European private equity firm with a strong global presence, managing significant AUM. CVC is active across various sectors including consumer, healthcare, and industrials, known for large buyouts and driving international expansion in its portfolio companies.

These leading private equity firms operate across ongoing investment cycles, constantly fundraising new capital from their limited liability partners, deploying it into companies with growth or turnaround potential, and later exiting through strategic sales or public offerings. Their size, reach, and experience make them some of the most influential actors in global finance. They employ teams of corporate finance advisers to execute their complex deals.

Common Misconceptions About Private Equity

The world of private equity can seem opaque, leading to several common misunderstandings. Addressing these helps clarify what is a private equity firm and what it is not.

Myth 1: Private Equity is public market trading.

- Reality: A private equity firm does not buy and sell shares on the stock market like typical retail investors. Instead, they acquire entire companies or large controlling stakes in private businesses, or they take public companies private. Their investments are long-term and illiquid, meaning they cannot be quickly bought and sold like shares on the S&P 500.

Myth 2: Private Equity is passive investment.

- Reality: Unlike investing in index funds or mutual funds where investors often take a passive approach, private equity involves highly active management. Firms actively intervene in their portfolio companies, implementing operational improvements, financial restructuring, and strategic shifts to enhance value. They are deeply involved in the business’s transformation.

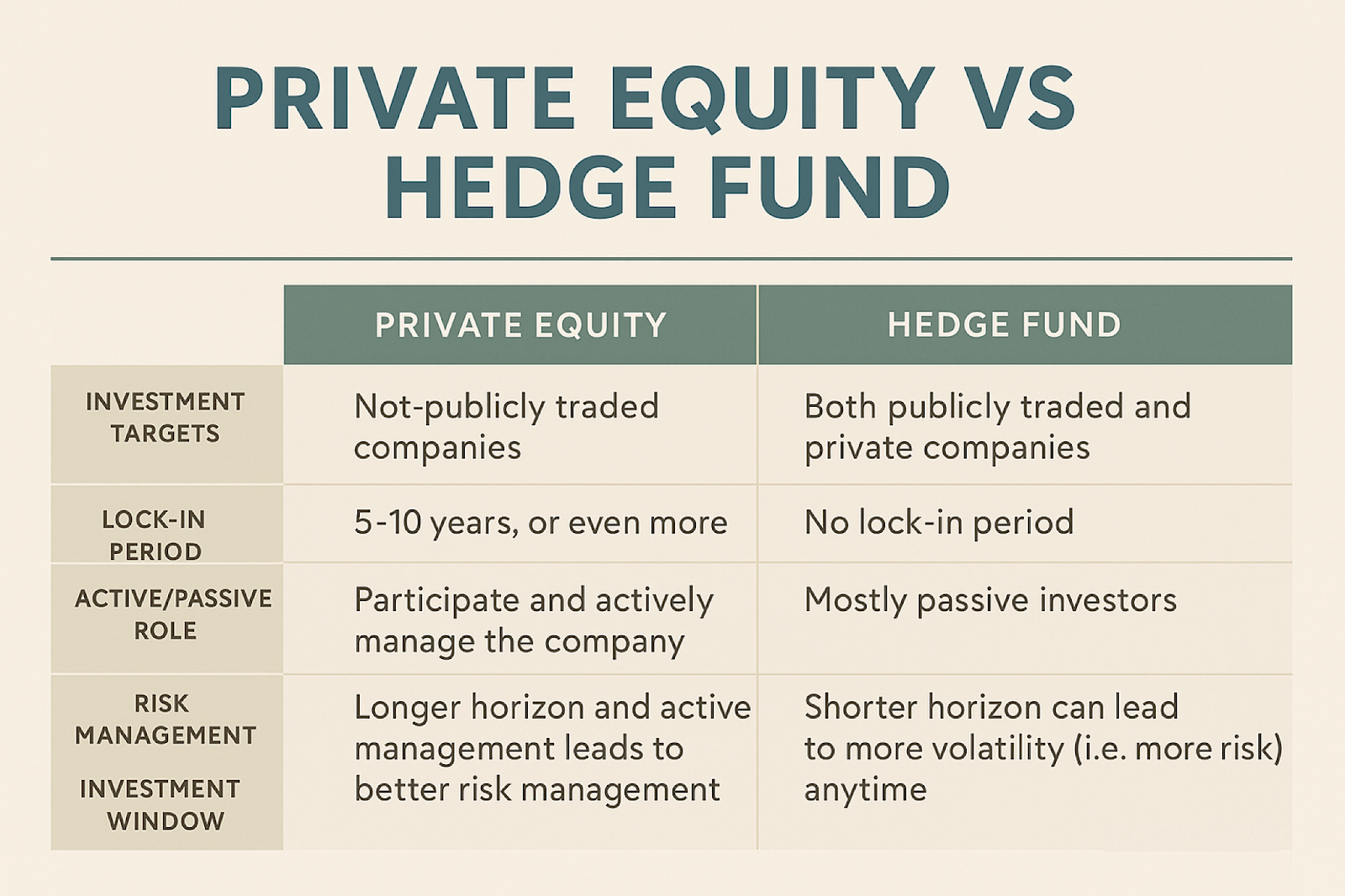

Myth 3: Private Equity and hedge funds are the same.

- Reality: While both manage capital for sophisticated investors, private equity firms focus on long-term, illiquid investments in companies, often taking control. Hedge funds, conversely, typically invest in a wide range of public securities and derivatives, employing complex investment strategies to generate returns in shorter timeframes, without seeking operational control of companies.

Myth 4: Private Equity is for everyone.

- Reality: Private equity funds have very high minimum investment requirements, often millions of dollars. They are typically only open to accredited investors and institutional clients due to their illiquid nature, high risk, and complex structures. They are not a general wealth management service for the public.

How Private Equity Firms Exit Investments And Return Capital To Investors

A crucial phase for a private equity firm is the exit strategies for its investments. The goal is to maximize returns for private equity investors by selling the improved portfolio company.

Common exit strategies include:

- Trade Sale: Selling the company to a strategic buyer, typically another corporation in the same industry seeking expansion or synergies. This is the most common exit route.

- Secondary Buyout: Selling the company to another private equity firm. This is a frequent occurrence in the private equity industry, allowing the new firm to pursue a new value creation thesis.

- Initial Public Offering (IPO): Taking the company public on a stock market (e.g., NASDAQ or NYSE) through an Initial public offering. This allows the public to buy shares and provides the private equity firm with liquidity. This form of exit activity is highly dependent on capital markets conditions.

- GP-Led Secondaries / Continuation Funds: A growing trend in the secondary market for private equity. Here, a General Partner sells a portfolio company from an older fund to a new continuation fund that they also manage. This provides liquidity to existing Limited Partners who wish to exit, while allowing the GP to continue holding the asset for further value creation. These secondary investments offer flexibility.

The secondary market for private equity fund interests has become increasingly active, allowing Limited Partners to sell their stakes in a fund before the fund’s official close. This provides liquidity in an otherwise illiquid asset class.

Important Regulatory Considerations

The private equity industry operates under specific regulatory frameworks, especially after the 2008 financial crisis.

- SEC Registration Requirements

Since the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, most private equity firms are required to register as investment advisers with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). This subjects them to ongoing oversight, including reporting obligations, compliance reviews, and examinations related to assets under management, fee disclosures, and potential conflicts of interest. - Fiduciary Responsibilities

Registered private equity firms generally owe a fiduciary duty to their limited partners. They are expected to act in the best interests of their investors, manage conflicts transparently, and ensure fair treatment in areas such as investment decisions, fee structures, and portfolio management practices. - Transparency and Reporting Standards

There has been an increased regulatory focus on transparency, particularly around fees, performance reporting, and governance. The SEC has introduced measures and guidance to ensure private equity firms provide investors with more consistent and detailed information. - Offshore Fund Compliance

Many private equity funds are domiciled in offshore jurisdictions such as the Cayman Islands or Luxembourg to provide tax efficiency and access to international capital. These structures must still comply with the regulatory requirements of both the host country and the jurisdictions where fundraising and operations occur.

Why Private Equity Matters

The private equity firm stands as a powerful, albeit often understated, force in the modern financial landscape. Far from being passive investors, these firms are active architects of corporate transformation, strategically acquiring, enhancing, and ultimately exiting companies to generate substantial returns for their sophisticated investors. Their methodologies, particularly leveraged buyouts and the pursuit of growth capital, demonstrate a potent combination of financial engineering and operational diligence aimed at unlocking hidden value. The intricate ecosystem involving Limited Partners, General Partners, and various investment strategies highlights the specialized nature of this industry.

Key Takeaways:

- A private equity firm is an investment management company that acquires controlling stakes in companies, aiming for long-term value creation.

- Firms are compensated through management fees and carried interest, aligning their success with their investors.

- Key strategies include Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs), Venture Capital, Growth Equity, and Distressed Investments, all characterized by active ownership and operational improvements.

- Private equity actively transforms businesses, distinguishing it from passive investment or the short-term trading of hedge funds.

- Exit strategies include trade sales, secondary buyouts, IPOs, and continuation funds, returning capital to investors via the secondary market.

- Access to private equity funds remains limited to institutional and accredited investors due to high minimums, illiquidity, and inherent risks.

Ultimately, understanding what is a private equity firm reveals a powerful engine of capital allocation and corporate restructuring. They are not simply investors; they are catalysts for change, leaving a significant imprint on the companies they touch and the broader economy.