Investors are often told to “do the homework” before buying a stock. That homework is not about predicting next week’s price swings or chasing online hype.

It’s about looking deeper into the strength of a business, its financial health, and its long-term potential. This approach helps separate solid companies from those built on shaky foundations.

In the sections that follow, we explore how this process works, why it matters for long-term investors, and what tools can help uncover the true story behind a stock.

What Is Fundamental Analysis?

Fundamental analysis is the process of evaluating a stock by examining the business behind it.

It involves looking at:

- Financial statements such as revenue, profits, cash flow, and debt levels

- Competitive position within the industry and market share trends

- Management quality and capital allocation decisions

- Growth drivers like innovation, expansion, or demand shifts

- The wider economy including interest rates, inflation, and consumer trends

- Valuation models such as discounted cash flow (DCF), dividend discount model (DDM), or peer multiples

The goal is to estimate a company’s intrinsic value, or what it is truly worth.

If a stock trades below that value, it may be considered undervalued. If it trades far above, it may be considered overvalued. The purpose is not exact prediction but forming a reasoned view of where opportunities and risks exist.

Why Fundamental Analysis Matters

Stocks are not just pieces of paper. They are ownership claims on real companies with employees, products, customers, and cash flows.

By studying fundamentals, investors can:

- Identify opportunities where quality companies are temporarily mispriced.

- Avoid value traps by recognizing when a high dividend or low P/E hides deeper financial trouble.

- Build conviction to hold investments during market volatility because decisions rest on evidence, not emotion.

- Match strategy with goals. For example, retirees may focus on dividend stability, while younger investors may focus on growth.

The Building Blocks of Fundamental Analysis

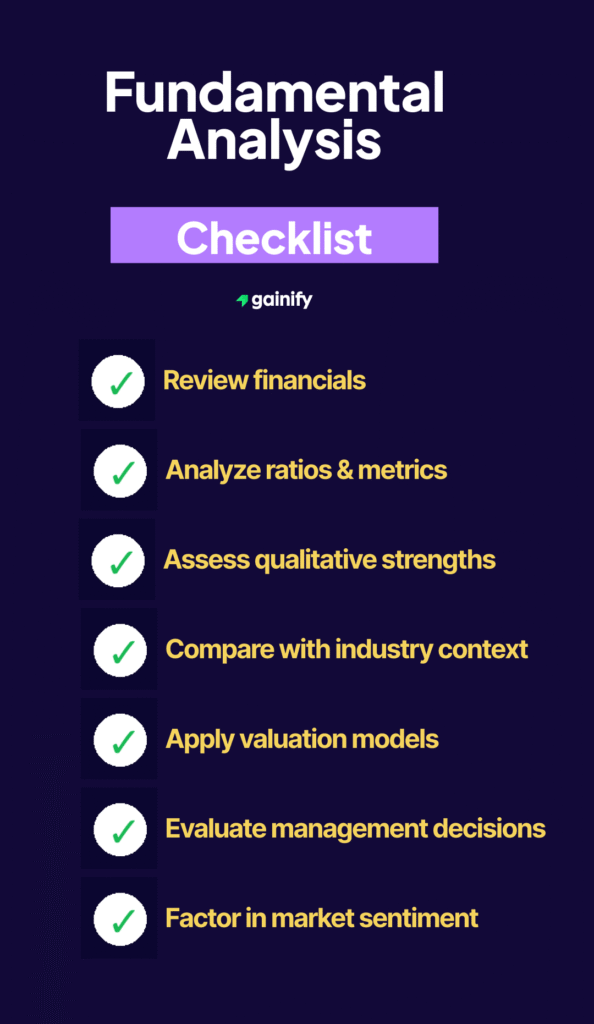

1. Financial Statement

The foundation of any analysis is the company’s reports. The income statement shows revenue and profit, the balance sheet reveals assets and liabilities, and the cash flow statement highlights real money in and out. Each tells part of the story, but together they show how solid the business really is.

2. Ratios and Metrics

Ratios turn financial data into insights.

- Margins: Gross, operating, and net margins measure efficiency at different levels.

- Returns: ROE and ROIC assess how well capital is deployed.

- Leverage and solvency: Debt-to-equity, interest coverage, and liquidity ratios show balance sheet strength.

- Capital efficiency: Asset turnover and working capital ratios test productivity.

Ratios are powerful tools, but they must be read in context and never in isolation.

3. Qualitative Factors

Some of the most important strengths are not numerical. Competitive moats, brand power, patents, supply chains, or management quality can sustain profits for decades. These are harder to measure and often subjective, but they explain why some firms thrive even when numbers look average.

4. Industry and Economic Context

No business operates alone. Rates, inflation, commodity prices, regulation, and consumer shifts affect performance. Industry cycles can support or undermine even the strongest firms. Context helps separate company-specific strength from external headwinds.

5. Valuation Models

The final step is deciding what the stock is worth. Models include discounted cash flow (DCF), dividend discount models (DDM), and multiples such as P/E, P/B, or EV/EBITDA. Asset-based valuations work for real estate or financial firms. Each model has weaknesses, so using several helps build a more reliable range.

6. Management and Capital Decisions

Leadership actions speak clearly. Dividend policy, buybacks, debt issuance, and reinvestment priorities reveal how management treats shareholders. Insider buying and selling can also send signals. Strong governance supports long-term value, while poor choices destroy it.

7. Market Sentiment

Fundamentals anchor value, but sentiment drives price in the short term. Analyst ratings, media coverage, and investor flows can push stocks above or below fair value for extended periods. Recognizing sentiment helps investors stay patient when the market misprices a company.

Fundamental vs. Technical Analysis

Fundamental analysis is often compared with technical analysis. The difference is focus.

- Fundamental analysis studies the company’s business reality. It asks what the stock should be worth based on revenues, profits, and strategy.

- Technical analysis looks at charts, price trends, and trading volume. It asks where the stock might move based on patterns and investor psychology.

Many professionals use both. For example, a fundamental investor may identify an undervalued company, then use technical tools to fine-tune entry and exit points.

Nuances and Limitations

Fundamental analysis is powerful, but it is not flawless.

- Subjectivity: Two analysts can interpret the same data differently, leading to different conclusions.

- Timing: A stock may remain undervalued for years before the market recognizes its true worth.

- Accounting risk: Profits can be manipulated through accounting choices, so cash flow often provides a more reliable signal.

- Market shocks: Even strong companies can see stock prices tumble during crises, creating disconnects between fundamentals and price.

This is why investors often combine fundamental analysis with diversification, risk management, and a long-term perspective.

Key Takeaways

- Fundamental analysis evaluates the real value of a company by looking at financials, industry, and qualitative strengths.

- It helps investors find mispriced opportunities, avoid risky traps, and invest with confidence.

- While not perfect, it remains the backbone of long-term investing because it is rooted in business reality, not market noise.