Inheriting stocks can feel like both a blessing and a burden. On one hand, it may represent the legacy of a parent, grandparent, or loved one who invested wisely. On the other, you may suddenly find yourself facing complex tax questions that you’ve never had to think about before.

If you’re wondering things like:

- “Do I pay taxes just for inheriting the shares?”

- “What happens if I sell them right away?”

- “How do I calculate gains or losses?”

…you’re not alone. In fact, many financial advisors say these are the exact same questions nearly every client asks the first time they inherit investments.

👉 Here’s the good news: the U.S. tax code actually has favorable rules for inherited stocks, including a special provision called the step-up in basis. This rule can wipe out decades of unrealized gains and dramatically reduce the taxes you might otherwise owe.

👉 Here’s the challenge: understanding how and when taxes apply, especially the difference between estate taxes, capital gains, and dividends can be confusing if you’ve never dealt with investments before.

What You’ll Learn in This Guide

By the end of this article, you’ll know:

✅ Why most heirs don’t owe tax immediately when they inherit stocks

✅ How the step-up in basis works and why it’s so valuable

✅ What taxes you’ll face when you sell inherited shares (and how to minimize them)

✅ The difference between estate tax and capital gains tax

✅ Smart strategies I use with clients to reduce tax bills and protect wealth

Whether you’re dealing with this situation today or preparing for the future, this guide will walk you through the process step by step, in plain English.

1. The Basics: What Does It Mean to Inherit Stocks?

When you inherit stocks, you’re essentially stepping into the shoes of the person who owned them before. But unlike other assets, stocks are unique because their value changes every single day in the market. This creates both opportunities and potential tax pitfalls.

For many people, the first reaction is confusion: Do I have to pay taxes immediately? Do I owe income tax on the value I just inherited? The answer is no. Simply inheriting shares does not create a taxable event. You don’t have to write a check to the IRS just because you now own the stock. Taxes only become relevant later, when you choose to sell those shares or when dividends are paid to you as the new owner.

It’s also important to recognize that stocks can be held in different ways before they’re passed on – sometimes they’re in a brokerage account, sometimes in a retirement account like an IRA. The rules are very different for each, and we’ll cover that later. But for now, let’s focus on standard brokerage-account stocks, because that’s where the step-up in basis rule comes into play.

2. Understanding the “Step-Up in Basis”

The step-up in basis is one of the most powerful tax benefits available to heirs. Without it, inheriting taxable brokerage assets could mean massive tax bills, especially if your parents or grandparents bought shares decades ago at very low prices. With the step-up, however, the playing field is reset in your favor.

Here’s how it works in simple terms: The government allows you to ignore the original purchase price. Instead, your “cost basis” (the value used to calculate gain or loss) is increased, or “stepped up,” to the fair market value of the stock on the date of death. If the stock has grown significantly over time, this can wipe out decades of unrealized gains.

Example: Imagine your mother bought Coca-Cola shares for $5 each back in the 1980s. Today, those same shares might be worth $70. If she sold them while alive, she’d owe tax on the $65 gain per share. But if you inherit them, your new cost basis is $70. If you sell immediately at $70, there’s no taxable gain. This reset dramatically reduces the tax burden for heirs and often encourages families to hold assets until death for this very reason.

3. Short-Term vs. Long-Term Capital Gains

Most investors know that stocks are taxed differently depending on how long you hold them. If you buy and sell within a year, it’s considered a short-term gain and is taxed like regular income, sometimes at very high rates. If you hold longer than a year, you qualify for long-term capital gains rates, which are significantly lower.

Here’s where inheritance is different and better. The IRS says that all inherited property is automatically treated as long-term, no matter how long you’ve personally held it. You could inherit stock today and sell it tomorrow, and it will still be taxed at long-term rates. This rule exists to simplify taxation and avoid penalizing heirs who had no control over when the original investment was made.

For many heirs, this rule means paying 15% or 20% instead of 24%, 32%, or even 37% had it been treated as short-term income. That’s a major difference, and it’s one of the most overlooked benefits of inheriting stocks.

4. What Happens When You Sell Inherited Stocks?

This is the heart of the issue – taxes only apply when you sell. The outcome depends entirely on the relationship between the stepped-up basis and your eventual sale price.

- Sell at the stepped-up basis: If you sell shares for exactly the fair market value they had on the date of death, you owe zero tax. It’s as if the IRS gives you a free pass.

- Sell above the stepped-up basis: Any amount above that baseline is considered a capital gain. You’ll pay long-term capital gains tax on that difference.

- Sell below the stepped-up basis: If the market drops and you sell at a lower price, you can actually use the loss to your advantage. These capital losses can offset other gains in your portfolio or reduce up to $3,000 of ordinary income per year, with the ability to carry forward extra losses into future tax years.

Example: You inherit 200 shares of Apple worth $150 each at the time of death (basis = $150). If you sell them at $180, you’ll report a $30 gain per share. If you sell at $130, you’ll report a $20 loss per share. In either case, you’re using the stepped-up basis as your starting point.

5. Estate Taxes vs. Capital Gains Taxes

Many heirs confuse estate taxes with capital gains taxes, but they are two very different things.

- Estate taxes are applied to the estate as a whole, not to individual heirs. They are only triggered if the estate exceeds the federal exemption limit, which in 2024 is $13.61 million per person (or potentially up to$27.22 million for married couples). That means more than 99% of estates will never owe federal estate tax. Some states, however, have their own estate or inheritance taxes with lower thresholds, so it’s worth checking your state’s rules.

- Capital gains taxes, on the other hand, are your responsibility as the heir. They only apply if you sell inherited stocks for more than the stepped-up basis. If you don’t sell, there is no capital gains tax.

Most families never encounter federal estate taxes, but almost everyone eventually faces capital gains tax decisions when managing inherited stocks.

6. Do You Pay Taxes If You Don’t Sell?

This is one of the most common questions I get in meetings with families. And the answer is simple: No, you don’t pay taxes just for inheriting.

As long as you hold onto the shares, there’s no capital gains tax triggered. You could keep them for years, decades even, and you won’t owe anything until you decide to sell. That said, you may owe taxes on dividends, since many companies pay quarterly dividends to shareholders. Dividends are considered taxable income and must be reported annually, but they are usually taxed at favorable rates if they qualify as “qualified dividends.”

This distinction is important: you’re not taxed for receiving the stock itself, only for the income it produces or the profit you realize when selling.

7. Special Situations to Know About

Inheritance isn’t always straightforward, and several special cases can change the tax outcome:

- Jointly Owned Accounts: If stocks were owned jointly (for example, by spouses), only part of the position may receive a step-up in basis, depending on state law. In community property states, often the entire account gets stepped up; in other states, only the deceased’s half does.

- Alternate Valuation Date: Executors have the option to use an alternate valuation date (six months after death) if it reduces the estate’s overall tax liability. This can benefit heirs if stock prices dropped significantly during that window.

- Gifting Before Death: If stocks are given to you as a gift before death, you inherit the original owner’s cost basis, not a stepped-up one. This can create much larger tax bills later, which is why estate planners often advise holding appreciated assets until death rather than gifting them early.

8. Strategies to Minimize Taxes on Inherited Stocks

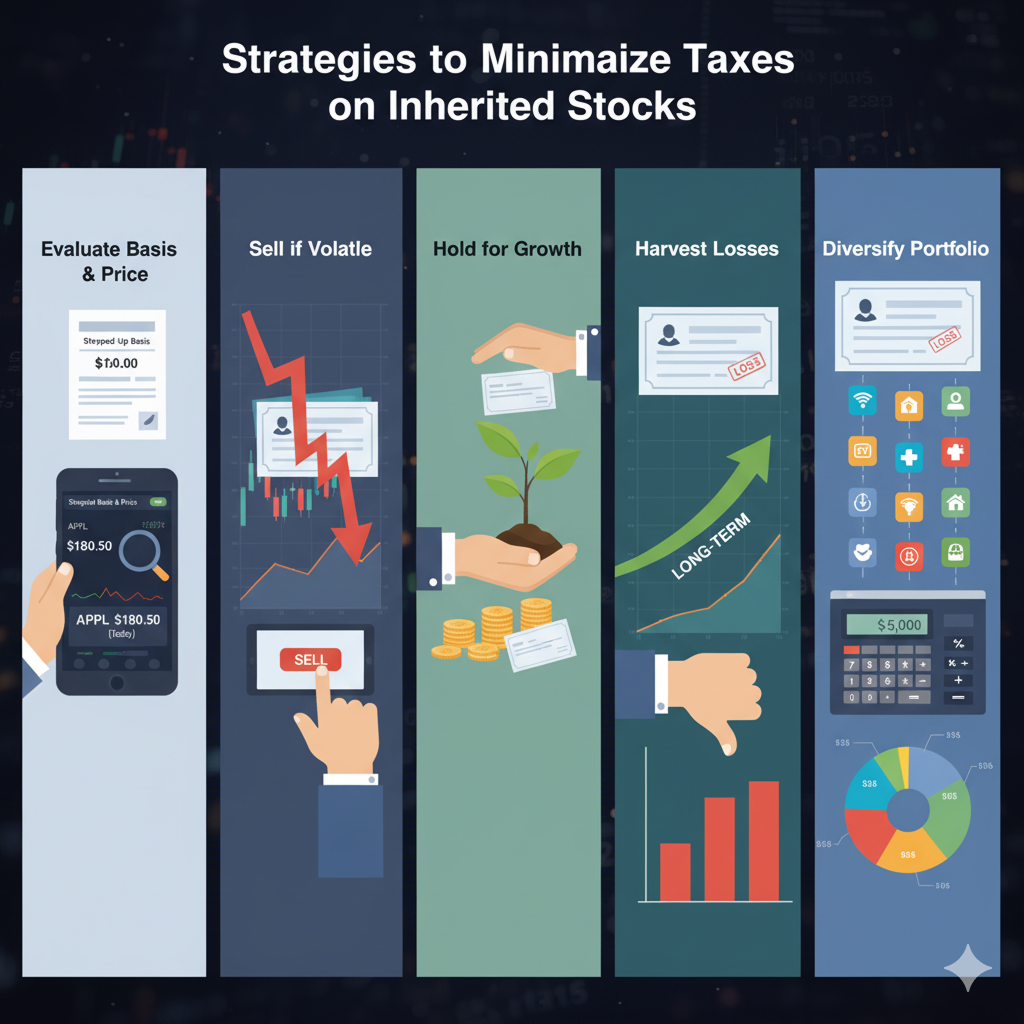

As a financial advisor, here are strategies I regularly recommend to heirs:

- Evaluate quickly: As soon as you inherit, find out the stepped-up basis and compare it to today’s price.

- Sell if you expect declines: If the stock looks overvalued or volatile, selling early may lock in the tax-free basis.

- Hold for growth: If it’s a strong company with long-term prospects, holding can build wealth, with all gains taxed at favorable long-term rates.

- Harvest losses: If the stock drops below your basis, selling can create tax losses that offset other income.

- Diversify: Many heirs inherit concentrated positions (e.g., one company stock that makes up half their portfolio). Diversifying reduces risk, even if it means selling and paying some tax.

9. Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Do I pay income tax on inherited stocks?

No. Stocks themselves aren’t taxed as income. You only pay capital gains tax if you sell for more than the stepped-up basis.

Q: What about dividends from inherited stocks?

Yes. If the company pays dividends after you inherit, you must report that income. Qualified dividends get the same favorable tax treatment as long-term capital gains.

Q: What if I inherit stocks in an IRA or retirement account?

That’s a separate issue. Inherited IRAs don’t receive a step-up in basis. Instead, distributions are taxed as ordinary income, and under the SECURE Act most non-spouse beneficiaries must fully withdraw the account within 10 years, with a few exceptions such as certain eligible designated beneficiaries.

Q: Can I transfer inherited stocks to my own account?

Yes. Once probate is complete, the shares can be moved to your brokerage account. The stepped-up basis information should transfer with them, and your broker can provide documentation.

10. The Bottom Line

Inherited stocks come with one of the best tax advantages in the code: the step-up in basis. This rule often means you’ll owe little to nothing if you sell right away, and only long-term capital gains if you sell later at a profit.

Here’s the key takeaway from decades of advising families: Don’t rush. Don’t sell out of fear. Instead, take time to understand your basis, think about diversification, and consult with a tax professional. Proper planning can turn an inheritance into a powerful wealth-building opportunity rather than a tax headache.