Tariffs are TAXES on imports that raise the cost of foreign goods entering a country.

They are often framed as a way to make other nations pay, but in practice the economic burden usually falls on domestic companies and consumers.

Governments use tariffs for several reasons. They are often applied to protect domestic industries, support strategic sectors, or respond to unfair trade practices such as dumping or foreign subsidies.

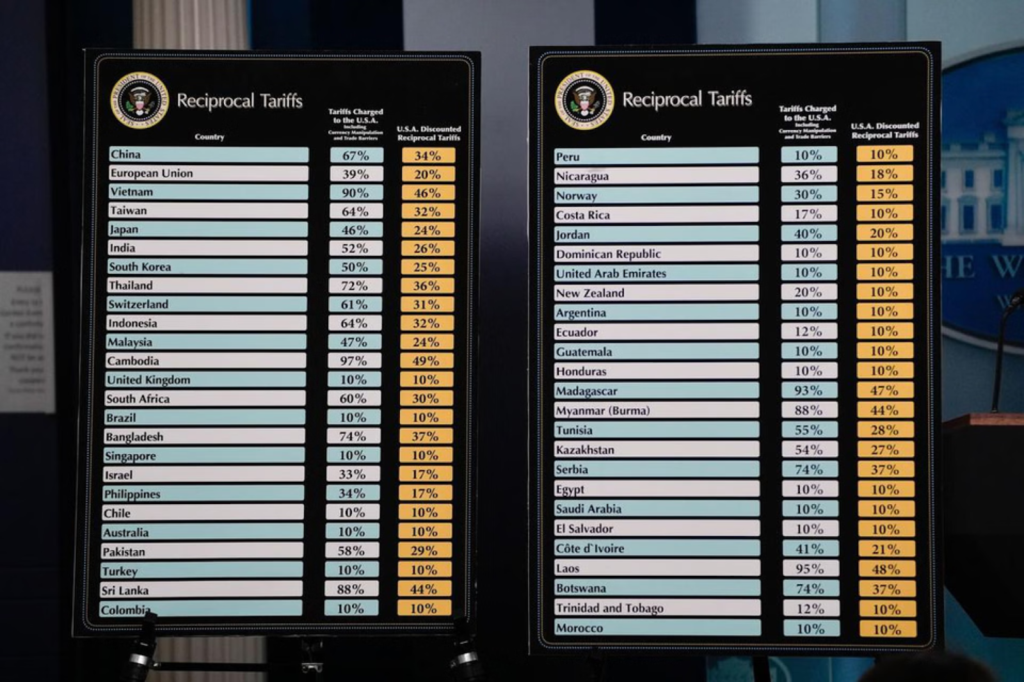

In some cases, including U.S. policy under the Trump administration, tariffs have also been used as leverage to influence trade negotiations, supply chain decisions, and broader geopolitical outcomes.

Regardless of the motivation, the economic effects follow a similar path. By increasing import costs, tariffs influence pricing decisions, inflation trends, corporate profit margins, and investment behavior across the economy. These effects extend beyond trade flows and appear in earnings results, consumer prices, and financial market expectations.

This article explains what tariffs are, how they work, who ultimately pays for them, and why they tend to push prices higher, using recent U.S. and global examples. Understanding who pays, who benefits, and how tariffs ripple through the economy has become essential for investors.

Key Highlights

- Tariffs are taxes on imports and in most cases the costs flow through to domestic companies and consumers.

- Tariffs can create localized winners in protected industries, but they often impose broader costs on downstream manufacturers and households

- Higher import costs feed inflation, affecting consumer prices, profit margins, and investor sentiment worldwide.

- For investors, tariffs matter because they reshape earnings expectations, drive sector rotation, and increase macro uncertainty

What Is a Tariff?

A tariff is a tax imposed by a government on imported goods when they cross a national border.

In the United States, tariffs are collected at the port of entry by U.S. Customs and Border Protection and are paid by the importer of record. The tax increases the cost of the imported product, which often leads to higher prices for businesses and consumers.

For example, if the U.S. imposes a 20 percent tariff on imported cars, a foreign-made vehicle priced at $20,000 would face a $4,000 tax at the border. That raises the importer’s cost to $24,000, a difference that is often passed on to consumers through higher prices.

By making imported goods more expensive, tariffs give domestic producers a pricing advantage over foreign competitors. This is why tariffs are commonly referred to as customs duties, since they are taxes collected by customs authorities on goods entering a country.

Technically speaking, a tariff is applied at the border and paid by the importer of record. In the U.S., the importing company pays the tariff to U.S. Customs and Border Protection when the goods enter the country. Once collected, tariff revenues go to the government’s coffers. Historically, tariffs were a major source of government revenue, before the federal income tax existed, tariffs funded up to 90% of U.S. federal government revenue in the 19th century. Today, tariffs contribute only a small share (the U.S. collected about $80 billion in tariff revenue in a recent year, versus $2.5 trillion from income taxes).

In summary, a tariff is a trade tax that raises the cost of foreign goods, making imported products less competitive compared to local goods.

Types of Tariffs

Not all tariffs work the same way. There are different types of tariffs depending on how the duty is calculated:

- Ad Valorem Tariff or Precent Tariff: This is the most common type – an ad valorem tariff (percent tariff) is charged as a percentage of the value of the good. Ad valorem is Latin for “according to value.” For example, a 10% ad valorem tariff on a $500 smartphone means the importer must pay $50 in tax. Most U.S. import duties are ad valorem, such as a 25% tariff on imported steel (25% of the steel’s value). Ad valorem tariffs automatically adjust with the price of the good.

- Specific Tariff: A specific tariff is a fixed fee per physical unit of the good, regardless of its price. For instance, a tariff might be $0.50 per pound of cheese or $500 per car, no matter the car’s sticker price. Specific duties are often used for commodities like agricultural products or raw materials. For example, a country could levy a tariff of $2 per barrel of imported oil. Unlike ad valorem duties, specific tariffs do not change with the product’s price.

- Compound Tariff: A compound tariff combines both an ad valorem and a specific component. In other words, it’s a two-part tax: a percentage of the good’s value plus a fixed fee per unit. For example, a compound tariff could be 5% of the merchandise’s value + $1 per unit. As a concrete example, imagine an import duty on wine that is $0.10 per bottle plus 15% of the wine’s value – this would ensure a minimum amount is paid per bottle (the specific part) on top of a value-based rate (the ad valorem part). Compound tariffs are less common but are used to fine-tune protection.

Who Pays for Tariffs?

Although tariffs are imposed on foreign goods, the cost is rarely paid by foreign countries. In most cases, tariffs are paid upfront by domestic importers and then passed on through the economy.

Here’s how the cost typically flows:

- Importers pay first

The importing company pays the tariff to customs authorities when the goods enter the country. - Businesses absorb or pass on costs

Importers may accept lower profit margins or raise prices to offset the higher cost. - Consumers often pay more

When higher costs are passed through, consumers face higher prices for imported goods or for domestic alternatives.

Bottom line: Consumers and domestic businesses end up paying much of the cost of tariffs. Tariffs act like a sales tax on imported goods and just as a sales tax usually means higher consumer prices, an import tax usually raises the prices of imported goods.

Do Tariffs Cause Inflation?

YES.

History shows that tariffs tend to raise prices by increasing the cost of imported goods and the products that rely on them.

During the 2018–2019 U.S.–China trade war, multiple independent studies found that the vast majority of tariff costs were passed through to U.S. businesses and consumers. Research from the Federal Reserve, University of Chicago, and the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) concluded that U.S. import prices rose by nearly the full amount of the tariffs, with little evidence that foreign exporters absorbed the cost.

A similar pattern appeared during earlier episodes of protectionism. After the Smoot–Hawley tariffs of the 1930s, import prices increased sharply, contributing to higher consumer costs and a contraction in global trade. While today’s tariffs are far smaller in scale, the economic mechanism is the same.

When tariffs raise the cost of key inputs such as steel, aluminum, or electronics components, those higher costs move through supply chains. Manufacturers face higher production costs, retailers face higher wholesale prices, and consumers ultimately pay more at the checkout. Even when companies try to absorb part of the increase, reduced competition allows prices to rise more broadly.

Taken together, historical evidence shows that tariffs function much like a consumption tax. They may be imposed at the border, but their inflationary effects are felt throughout the economy over time.

Real-World Example: U.S. Tariffs on Chinese Electronics and Steel (Trump Administration)

The current tariff regime did not emerge suddenly. It developed through a renewed escalation in 2025 and has since settled into a more durable, restrictive framework that now defines the global trade environment.

How the Tariff Escalation Began

In 2025, the Trump administration reintroduced and expanded tariffs as a central tool of trade and industrial policy. One of the first moves was the reinstatement of tariffs on imported metals. Steel imports were set at a 25% tariff and aluminum at 10%, with exemptions for close allies largely removed. The stated objectives were national security, countering global overcapacity, and strengthening domestic manufacturing.

At the same time, the administration sharply escalated tariffs on Chinese imports. Duties were expanded across electronics, consumer goods, and critical technology components, with some categories facing extremely high rates. While certain consumer electronics initially received exemptions, many products remained subject to a 20% tariff classification tied to national security and public health considerations.

Markets initially treated these moves as a familiar replay of earlier trade conflicts. U.S. steelmakers benefited from expectations of higher prices and improved margins, while downstream industries flagged rising costs. Retailers and manufacturers began reassessing sourcing strategies as uncertainty around trade policy intensified.

How China Responded

China responded with retaliatory tariffs on U.S. exports, including agricultural products and industrial machinery. Officials made clear they would not concede under unilateral pressure. This back-and-forth reinforced uncertainty and raised concerns about a broader trade war, particularly through the second half of 2025.

Global markets reacted with higher volatility, while businesses delayed investment decisions and accelerated efforts to diversify supply chains away from direct China exposure.

Where It Ended Up

By 2026, the tariff escalation had not fully reversed, but it also had not spiraled indefinitely. Instead, tariffs settled into a sustained policy baseline.

Steel and aluminum tariffs remain in place, with higher input costs now embedded across industrial supply chains. Tariffs on Chinese goods continue to affect electronics, consumer products, and technology-related components, even as companies have diversified sourcing toward Southeast Asia, Mexico, and domestic production. These shifts have reduced concentration risk but have not meaningfully lowered costs, making higher prices a more permanent feature rather than a temporary shock.

China’s retaliatory measures also remain largely intact, resulting in a global trade environment that is more fragmented, less efficient, and more politically sensitive than in the past.

Bottom Line: What began as a renewed tariff offensive in 2025 has, by 2026, evolved into a new trade equilibrium. Tariffs are no longer viewed as short-term leverage or negotiating tactics. They are now a structural element of the global economic landscape, influencing inflation, corporate margins, and investment decisions.

For investors and businesses alike, the question is no longer whether tariffs will disappear, but how long they persist and which companies are best positioned to operate profitably in a world where higher trade friction is part of the status quo.

Economic Theory: Arguments For and Against Tariffs (Protectionism vs. Free Trade)

Tariffs and protectionism have been debated by economists for centuries. Here are the core points of economic theory regarding tariffs, including classical arguments for and against:

Arguments For Tariffs (Protectionist View):

- Protecting Domestic Industries and Jobs: The most traditional argument is that tariffs protect domestic industries from foreign competition, allowing them to survive and keep jobs at home. This can be especially appealing if foreign producers have an unfair advantage (lower wages, subsidies, etc.). By raising import prices, tariffs can prevent domestic factories from shutting down due to cheaper imports. A classic example is the “infant industry” argument: emerging industries in developing countries might need temporary tariff protection to grow and achieve economies of scale before they can compete globally. Tariffs can also shield workers from sudden job loss due to import surges; this social argument for protectionism often resonates in politics.

- National Security and Strategic Industries: Tariffs are justified to maintain domestic capability in industries crucial for national security – e.g. defense, energy, food supply, medical supplies. The argument is that relying entirely on foreign sources for these vital goods is risky. By protecting these industries, a country ensures it can produce essential products in a crisis. For instance, tariffs on defense-related materials or technologies might be levied so the country isn’t dependent on potential adversaries.

- Retaliation and Bargaining with Foreign Countries: Tariffs can be used as a tool to bargain with or punish other countries. If another nation is believed to practice unfair trade (such as dumping products below cost, or subsidizing exports, or having high tariffs of their own against your goods), imposing tariffs can serve as leverage. The threat of tariffs might push a trade partner to negotiate better terms or cease unfair practices. For example, tariffs were threatened (and briefly imposed) on Mexico by the U.S. to pressure for cooperation on immigration issues. While not a classical economic “good,” this is a strategic/political use of tariffs. In theory, if a country faces a trade partner with very high barriers, slapping tariffs could force reciprocal concessions (hence terms like “reciprocal tariffs”). Tariffs can also be retaliation via WTO rules – if you win a trade dispute, the WTO may allow you to impose tariffs on the offender to recoup losses.

- Improving the Trade Balance (Reducing Deficits): Some argue that tariffs can help reduce a trade deficit by curbing imports. If imports become more expensive and fall, the trade deficit (imports minus exports) might shrink. This mercantilist-flavored view sees tariffs as a way to address trade imbalances and protect domestic output. (Economists generally counter that macroeconomic factors, like savings and investment balances, drive trade deficits, not tariffs, but the argument persists in public debate.)

- Countering Foreign Dumping or Subsidies: When foreign producers “dump” products (sell below cost) or receive heavy government subsidies, they can undercut domestic firms unfairly. Anti-dumping duties and countervailing duties are special tariffs aimed at these situations. The theoretical justification is to level the playing field. If, say, a foreign government subsidizes steel exports, a tariff of equal magnitude can negate the artificial price advantage. This is seen not as “protectionism” but as defense against unfair trade. Many WTO rules permit such tariffs if proven.

- Optimal Tariff (Terms-of-Trade Gain): A more technical argument: if a country is a large buyer of a certain good on the world market, by imposing a tariff it can lower the world price of that good (because it reduces its own demand, forcing foreign suppliers to cut price). The country then pays less per unit to foreigners. This is known as an “optimal tariff” – theoretically, a tariff rate exists that maximizes the country’s gain by improving its terms of trade. In this scenario, the tariff-imposing country could, in principle, come out ahead, gaining from lower import prices and tariff revenue more than it loses in consumer surplus).

Arguments Against Tariffs (Free Trade View):

- Higher Prices for Consumers: The most direct argument against tariffs is that they raise prices for domestic consumers. By design, a tariff makes imported goods more expensive. Consumers either pay more for the imported item or switch to a now-more-expensive domestic alternative. In either case, consumer surplus falls – people get less value because of higher prices or fewer choices. The basic economic analysis of a tariff shows that consumers lose more than producers gain. For example, a tariff on foreign cars means car buyers have to pay hundreds or thousands more per vehicle (either buying the import with tariff or a pricier domestic model). This reduced purchasing power is a major cost of tariffs. Economists often emphasize that protectionism is essentially a tax on consumers.

- Economic Efficiency and Deadweight Loss: Tariffs distort the allocation of resources. In a free market, countries specialize in producing goods where they have a comparative advantage (lower opportunity cost) and trade for others – this leads to efficient production globally and lower prices (this is David Ricardo’s famous comparative advantage theory). Tariffs interfere with this specialization by encouraging domestic production of things that could be made more cheaply abroad. The result is economic inefficiency: resources are diverted into industries where the country is less efficient, solely because the tariff artificially tilts the playing field. Graphically, as taught in Econ 101, a tariff creates deadweight loss – lost welfare that is not transferred to anyone, it’s pure inefficiency. In the supply-demand diagram, some consumer loss isn’t offset by producer gain or government revenue; it’s a net loss (areas of lost trades that would have been mutually beneficial at world prices). The consensus among economists is that tariffs overall reduce national welfare. In fact, a survey of leading economists found essentially 0% agreed that steel/aluminum tariffs would improve Americans’ welfare – none thought tariffs made the U.S. better off; the vast majority disagreed with the notion.

- Retaliation and Trade Wars (Lose-Lose Outcomes): When one country raises tariffs, others often retaliate, leading to a spiral of barriers that hurt all sides. This is what happened in the 1930s after the U.S. passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff – U.S. trading partners retaliated, causing global trade to collapse and worsening the Great Depression. Retaliatory tariffs harm exporters in the tariff-imposing country. The end result of a tariff war is usually shrinking trade, higher prices, and reduced economic welfare for everyone – a lose-lose scenario.

- Loss to the Economy and GDP: Tariffs can protect specific jobs, but at a higher cost to the economy in aggregate. Resources locked in less efficient protected industries mean overall productivity suffers. A comprehensive study across 151 countries over decades found that tariff increases are associated with statistically significant declines in domestic output and productivity, as well as higher unemployment. In other words, higher tariffs tend to stunt economic growth. Tariffs can also reduce export competitiveness. Indeed, tariffs often lead to no improvement in the trade balance because exports may fall along with imports.

- Costs to Downstream Industries and Exporters: Tariffs on inputs (like tariffs on steel, aluminum, semiconductors) raise costs for downstream industries – the manufacturers who use these inputs. This can lead to job losses in those industries or higher prices for their products. For example, a tariff that helps 10,000 workers in steel production might raise costs for 500,000 workers in steel-using industries and endanger some of those jobs.

- Lost Innovation and Competitiveness: Protection from competition can breed complacency. Domestic firms behind a tariff wall might have less incentive to innovate or improve efficiency, since they don’t face the full pressure of global rivals. Over time, this can make the protected industry less competitive internationally. Free trade advocates argue that competition spurs innovation, and consumers benefit from a greater variety of goods and technologies. Tariffs, by insulating local companies, may lead to lower-quality or higher-cost products in the long run.

- Global Inefficiency and Conflict: On a global scale, widespread use of tariffs reduces overall trade and economic growth. It can also strain international relations – trade wars can spill into political hostility. The post-WWII consensus (GATT and WTO) was built on the belief that lower tariffs foster peace and prosperity, whereas protectionism in the 1930s contributed to economic collapse and tensions. Free traders argue that everyone is better off in the long run with open markets, aside from necessary safeguards against truly unfair practices.

In summary, proponents of tariffs highlight targeted benefits: protecting jobs, industries, and security, correcting unfair trade, and sometimes improving terms of trade. Opponents highlight the broad costs: higher prices, inefficiencies, net economic loss, and retaliation. The classical view is that free trade maximizes wealth, and tariffs are largely self-defeating except in special cases. Modern empirical evidence tends to support the idea that tariffs hurt overall GDP and productivity while saving relatively few jobs at high cost.

Who Benefits from Tariffs? Winners: Domestic Producers and Sensitive Sectors

If consumers and import-using companies lose out from tariffs, who wins? Tariffs create a clear set of winners – typically, domestic industries that compete with imports. By penalizing foreign competitors with an extra cost, tariffs “protect” the home producers of that good. Here are the main beneficiaries of tariffs:

- Domestic Manufacturers of the Tariffed Goods: The most direct winners are companies and workers in industries that face import competition. When a tariff is imposed, imported goods become costlier, and domestic producers can gain market share or charge higher prices. They are effectively shielded from some of the foreign competition. For example, U.S. steelmakers benefited from the 25% steel tariff: with imports more expensive, American steel became relatively cheaper for U.S. buyers. Domestic steel mills were able to raise output and prices; in fact, the tariff was estimated to boost U.S. steel firms’ pre-tax profits by about $2.4 billion. Their stock prices jumped on tariff announcements, reflecting this advantage.

- Workers in Protected Industries: By extension, employees in sectors like steel, aluminum, textiles, etc., can benefit from greater job security or even job growth thanks to tariffs. The protected industry may open new factories or at least avoid layoffs because domestic demand shifts towards their products. Tariffs are often politically touted as tools to save jobs in industries threatened by import competition. For instance, tariffs on imported tires or steel in the past were justified as necessary to preserve American jobs in those factories.

- Industries Important for National Security or Other Strategic Goals: Sometimes the “winners” from tariffs are sectors considered vital for the country. Governments may impose tariffs to ensure domestic capacity in critical areas like defense, energy, or food supply. For example, tariffs on steel and aluminum were justified on national security grounds – the idea was to ensure the U.S. maintains a viable metals industry for defense needs. In such cases, the domestic arms of strategically important industries benefit by becoming more robust. Governments commonly shield sectors like agriculture, steel, automobiles, or technology if they deem them crucial for economic or security reasons.

- Government (Tariff Revenue): The government imposing the tariff does collect revenue from it, which is technically a benefit. Tariffs can fill government coffers – historically, they financed the U.S. government in its early years. Today, revenue is a secondary motive in countries like the U.S. (tariffs are a “trifle” compared to income tax revenue), but it’s still money that can fund programs.

- Domestic Suppliers to Protected Industries: There can be indirect winners too. If a tariff helps a domestic industry expand, companies that supply inputs or services to that industry might see more business. For example, a boom in domestic steel production could benefit local iron ore mines or equipment manufacturers that sell to steel mills.

It’s important to underscore that these benefits are concentrated. A tariff’s benefit is usually enjoyed by a relatively small, specific group, whereas the costs are spread across millions of consumers or many downstream businesses. This imbalance is why tariffs persist politically: the winners are few but have much at stake, so they advocate strongly, while the losers (consumers paying a bit more each for goods) are many but each individual has only a modest loss and may not notice or organize against it.

How Do Tariffs Affect the U.S. Stock Market?

Tariffs can ripple through the stock market with surprising speed. When new trade barriers are announced, investors rapidly reassess company earnings potential, cost structures, and global exposure. The result: clear winners and losers emerge, often sector by sector.

Tariff Winners: Who Benefits?

Tariffs are primarily designed to protect domestic industries and those that compete directly with foreign imports are often the first to benefit.

When tariffs are imposed, imported goods become more expensive. That shift tilts the playing field in favor of local producers, allowing them to capture market share, raise prices, and increase margins. For these companies, tariffs can provide a short-term profitability boost and a more secure competitive environment.

Industries such as basic materials, heavy manufacturing, industrial inputs, and select segments of consumer goods often stand to gain. With reduced competition from abroad, domestic suppliers may see increased order volumes, higher pricing power, and renewed investment in local capacity. Even more technical sectors, like advanced manufacturing or semiconductor equipment, can benefit over time if tariffs incentivize reshoring of production or supply chain diversification.

Tariff Losers: Who’s Hurt?

Global Operators and Import-Reliant Industries: while tariffs may provide short-term protection to select domestic industries, they often impose significant costs on a much wider swath of the economy, particularly for businesses that depend on global supply chains or international markets.

Import-heavy industries are among the most directly affected. Companies that rely on foreign raw materials, components, or finished goods typically face higher input costs once tariffs are in place. This can compress profit margins, disrupt production schedules, and force difficult pricing decisions.

Manufacturers with global operations, especially in sectors like automotive, aerospace, industrial machinery, and electronics, often experience both rising costs and reduced flexibility. These industries are deeply integrated into international supply networks, and tariffs can create bottlenecks, delays, and significant cost inefficiencies.

Consumer-facing companies that source large portions of their inventory from abroad are also at risk. Tariffs on consumer goods often lead to either higher retail prices, which can soften demand, or lower margins if companies choose to absorb the added costs.

Export-oriented sectors face yet another challenge: retaliation. When trading partners respond with their own tariffs, U.S. exporters, including those in agriculture, machinery, and technology, often suffer from reduced market access, declining demand abroad, and increased uncertainty.

In summary, while tariffs may shield select industries from foreign competition, they often disrupt broader supply chains, increase operational costs, and expose companies to geopolitical risks. In a globally connected economy, these side effects can ripple far beyond the targeted sectors.

Market-Wide Impact of Tarriffs: Volatility & Rotation

Tariff headlines drive market-wide volatility. During the 2018–2019 U.S.–China trade war, the S&P 500 repeatedly swung 1–3% daily based on tariff news, causing sector rotations and safe-haven rallies.

- Risk-Off Moves: Investors often shift capital into Treasuries, gold, or defensive sectors like utilities and consumer staples during trade stress.

- International Spillovers: Global export hubs like Germany, South Korea, and China suffered when global trade slowed. Chinese equities underperformed significantly during the original trade war.

- Multinationals vs. Domestic Firms: Companies with global footprints tend to lag during trade conflicts, while domestically-focused businesses may outperform thanks to reduced foreign competition or currency shifts.

Investor Sentiment: Uncertainty is the Enemy

Tariffs increase uncertainty and markets hate uncertainty. Corporations delay investments, analysts lower earnings expectations, and valuations compress. During the 2018 trade war, business investment in the U.S. stalled. In 2019, as tensions eased with a partial deal, markets rebounded sharply. The phrase “no one wins a trade war” became common on Wall Street and for good reason.

How Do Tariffs Impact the Economy: GDP Growth, Supply Chains, and Employment

Beyond prices and specific sectors, tariffs have wider effects on the overall economy. By altering the flow of goods and costs, tariffs can influence GDP growth, disrupt supply chains, and affect employment across various industries:

- Impact on GDP Growth and Output: Tariffs tend to dampen economic growth in the long run. By increasing costs and reducing efficiency, they act as a drag on both consumption and production. Multiple studies have found a negative correlation between higher tariffs and GDP. For instance, a comprehensive study across many countries showed tariff hikes lead to persistent declines in domestic output and productivity. The logic: consumers have less purchasing power, since they pay more for goods, and resources are reallocated from competitive sectors to protected ones, which might be less productive. This misallocation plus reduced trade generally means lower GDP than otherwise. During the trade war, we saw that business investment in the U.S. slowed due in part to trade uncertainty and higher costs, which likely shaved some points off GDP growth. Likewise, exporters facing retaliation sold less, hitting farm GDP and manufacturing output. Globally, the IMF and World Bank warned that the U.S.-China tariffs could shave tenths of a percent off global GDP as well, by disrupting supply chains and lowering trade volumes.

- Productivity and Innovation: Over time, tariffs can reduce productivity growth by shielding less efficient firms from competition. This can slow the rate of innovation and adoption of best practices, indirectly affecting GDP growth. When industries don’t have to compete with the best in the world, they may not invest as aggressively in new technologies. The previously mentioned 2021 study linked tariffs to lower productivity and higher unemployment – a toxic combination for growth. Conversely, exposure to trade tends to boost productivity through competition and knowledge transfer. So tariffs forgo those gains.

- Trade Volumes and Supply Chains: Tariffs distort supply chains by making certain sourcing options more expensive. Companies adjust by seeking alternative suppliers in other countries or by bringing production onshore despite higher costs. This re-engineering of supply chains can be disruptive and costly. For example, during the U.S.-China trade war, some U.S. importers shifted production from China to Southeast Asian countries to avoid tariffs. While this mitigated tariff costs for those firms, it often meant less efficient supply chains, as they weren’t sourcing from the absolute lowest-cost or best-suited supplier. It also caused upheaval – companies had to qualify new suppliers, manage logistical changes, and sometimes accept higher input prices from the next-best source. In a broader sense, tariffs break existing global value chains that were optimized over decades. This can introduce bottlenecks or capacity issues in the short run. Efficiency losses in supply chains can show up as slower production growth or even shortages, which again feed into higher costs or lost output.

- Uncertainty and Investment: The use of tariffs, especially unpredictably, creates uncertainty for businesses. Companies uncertain about trade costs might delay or cancel investments in new projects or expansion. During 2018–19, the unpredictable “will tariffs go up or will there be a deal” environment led many firms to hold off on capital expenditure. The Fed Beige Book explicitly noted tariff and trade policy uncertainty was causing reduced capital spending and hiring. This cloud over the investment climate can have a chilling effect on growth. Investment is a component of GDP, so when it slows, GDP growth slows. Moreover, less investment today can mean less capacity and innovation for tomorrow, a longer-term hit.

- Employment Effects: Tariffs reallocate jobs between sectors – they save or create jobs in protected industries, but can cost jobs in others. We’ve given examples: thousands of jobs added in steel, but potentially tens of thousands lost in steel-using sectors because of higher input costs and resultant cutbacks. If a company’s input costs rise significantly, it might reduce its workforce or shelve expansion plans to cut expenses. Retaliatory tariffs also kill jobs in export industries. The net effect on total employment from a tariff depends on the balance – often, analysis finds a small net negative. For instance, the Peterson Institute calculated that the steel and aluminum tariffs might eventually cost more U.S. jobs than they saved, as downstream job losses outweigh upstream gains. On the flip side, in the short run, workers in newly protected factories might see increased hours or wages as demand shifts to domestic goods. So there are winners and losers. The political calculus of tariffs is often about trading some job losses for more politically visible job gains.

- Consumer Spending: Tariffs can act like a tax on consumers, leaving them with less disposable income for other spending. If a family has to spend an extra $300 a year due to various tariff-induced price hikes, that’s $300 less for other goods or savings. With millions of consumers, that reduction in purchasing power can have a macroeconomic effect, softening consumer spending growth – the largest component of GDP. Still, it’s an effect to consider: consumer-facing industries not directly tariffed might indirectly feel the pinch as households pay more for tariffed items and cut back elsewhere.

- Competitiveness and Trade Balance: Ironically, while tariffs aim to help domestic industries, in some cases they can hurt the competitiveness of other domestic sectors, including exporters. As noted, higher input costs can make U.S. exports more expensive. Also, trading partners’ retaliation makes U.S. exports costlier in those markets (via foreign tariffs). So some U.S. companies lose market share overseas, which can widen the trade deficit in other categories. As one WTO analysis put it, tariffs don’t fix trade deficits; they just shift trade around. Additionally, tariffs can cause currency adjustments – often the tariff-imposing country’s currency might strengthen as a result of trade changes (the dollar did rise in 2018), which ironically makes imports cheaper and exports more expensive, counteracting the tariff’s effect on trade balance to some extent.

- Inflation and Monetary Policy: We discussed inflation in detail. From a macro perspective, if tariffs push inflation up, central banks might respond by raising interest rates sooner or more than they otherwise would. Higher interest rates can slow investment and borrowing, adding another brake on growth. For example, had the trade war significantly driven inflation up, the Fed might have tightened policy, dampening growth. In contrast, if tariffs were deflationary (by causing a recession via trade war), central banks might cut rates or do stimulus to offset.

- Global Supply Chain Reorientation: Over a longer horizon, persistent tariffs can lead firms to diversify supply chains for resilience (not just cost). The U.S.-China tensions made many multinationals rethink heavy reliance on one country. This could result in a more fragmented global trading system (some call it “decoupling”). This fragmentation might prevent some efficiency gains from deep integration, potentially leading to slightly higher production costs globally and lower global growth than a fully integrated scenario. Economically, the world might settle into trading blocs, with each bloc having higher internal efficiency but less cross-bloc trade, influenced by tariffs and trade barriers. That is more of a geopolitical economic implication.

In sum, tariffs can slow GDP growth, reshape supply chains (often at a cost), and cause both job gains and losses with a likely net loss in aggregate employment relative to free trade. They act as a tax and a barrier, which generally means less trade, less specialization, and therefore less output than otherwise. While they can temporarily boost a targeted industry, the broader economy may see slightly lower growth and productivity as a result of widespread tariffs.

This is why institutions like the IMF, World Bank, and most economists caution against tariff escalations – they view free trade as a driver of global growth, and protectionism as a risk. The experience of the early 1930s – when high tariffs contributed to a collapse in world trade and deepened the Depression – serves as a historical warning of how bad it can get if everyone raises tariffs dramatically. The recent tariff flare-ups were much smaller in scale, but even those had noticeable negative effects on investment and sentiment in 2019.

Do Tariffs Cause Inflation?

In short: yes, tariffs tend to raise prices.

While the magnitude can vary, most studies and real-world examples confirm that tariffs contribute to inflation by increasing the cost of imported goods, and in turn, the cost of products that rely on them.

How It Happens

Tariffs are essentially a tax on imports. When a tariff is imposed — say, 25% on imported steel — the price of that steel rises for domestic buyers. This cost increase often trickles down through the supply chain:

- Manufacturers pay more for raw materials or components.

- Retailers face higher wholesale prices for goods sourced abroad.

- Consumers ultimately pay more at the checkout, as companies pass on those added costs.

Even when companies try to absorb some of the tariff impact, profit margins shrink, reducing investment or hiring capacity, both of which can indirectly affect the economy.

Indirect Inflation Pressure

Tariffs don’t just raise prices on directly affected goods. They can also lead to:

- Broader supply chain cost increases, especially in industries like autos, tech, and construction.

- Reduced competition, allowing domestic producers to raise prices more freely.

- Retaliation-driven price shifts, where countries hit back with their own tariffs, disrupting global price stability.

What Economists Say

Most economists agree that tariffs are inflationary by nature, even if the price increases are modest at the macro level. According to a J.P. Morgan report, the cumulative effect of tariffs imposed during the Trump administration added roughly 0.3–0.5 percentage points to core inflation over two years.

While tariffs are sometimes used to protect domestic jobs or pressure foreign rivals, they also act as a regressive tax, hitting lower-income consumers hardest, as they spend a larger share of their income on goods most affected by tariffs (like food, clothing, and appliances).

Conclusion: Tariffs – A Tool of Trade, Not Without a Cost

Tariffs are a double-edged sword. On one side, they offer targeted protection for domestic industries, helping preserve jobs, boost local production, and provide leverage in trade negotiations. For sectors like steel or agriculture, they can be a lifeline in a globally competitive market.

But that protection comes at a price. Tariffs act as a tax on imports, raising costs for businesses and consumers alike. They can fuel inflation, disrupt supply chains, provoke retaliation, and dampen economic growth. Most economists agree: while tariffs may help a few, they impose broader costs on the many.

Ultimately, tariffs are a trade-off between short-term strategic gain and long-term economic efficiency. Used carefully and transparently, especially within WTO rules, they can serve a purpose. But overuse risks acting as a self-imposed tax on the economy.

In a globalized world, the real question isn’t whether tariffs are good or bad — it’s when, where, and how they should be used to serve the national interest without harming the broader economy.