Book value is one of those terms that sounds simple but carries layers of meaning. Many people think of it only as shareholder equity, yet in accounting it goes further.

To really use book value effectively, you need to understand not just the number itself, but how it is calculated, what it includes, and what it leaves out. That is where its real value and its limitations become clear.

What Is Book Value?

Book value is the carrying amount of an asset or liability as reported on the balance sheet under U.S. GAAP.

- For assets, book value usually reflects the purchase price, reduced by depreciation, amortization, or impairment charges.

- For liabilities, it represents the obligation recorded in the books, most often measured at amortized cost and adjusted for discounts, premiums, or issuance costs.

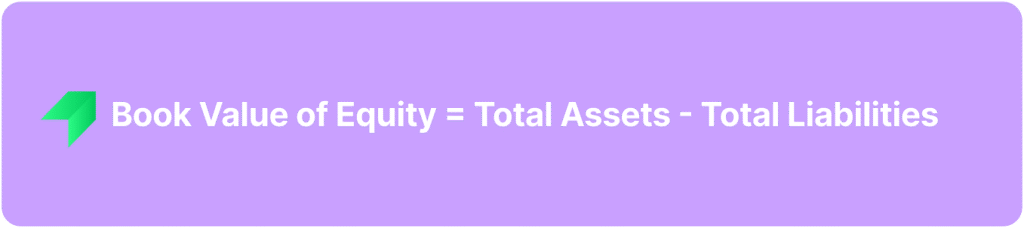

In a different context, book value is also used to describe equity value. Here it refers to the net worth of a company according to its accounting records:

Book Value of Equity = Total Assets − Total Liabilities

This measure represents what shareholders would theoretically receive if assets were sold at their book value and all liabilities were paid. Unlike asset or liability book values, which focus on individual line items, equity book value summarizes the company’s overall financial position.

How Book Value Works for Assets

Every asset on the balance sheet carries a book value, but not all are measured the same way. The method depends on the type of asset and the accounting model applied.

- Tangible assets: Machinery, equipment, and property are recorded at historical cost. Their book value declines over time through depreciation. For example, a building purchased 20 years ago may have a book value far below its current market price.

- Intangible assets: Purchased intangibles, such as patents or trademarks, are recorded at acquisition cost. They are amortized over their useful life or written down if impaired. Internally generated intangibles, such as brand reputation or customer relationships, are not recorded at all. This means the balance sheet can understate a company’s true resources.

- Current assets: Cash, receivables, and inventory are generally reported at values close to their realizable amount. Their book value is usually more accurate than that of long-lived assets.

- Financial assets at fair value: Certain financial instruments, including marketable securities and derivatives, are marked to market under GAAP. Their book value is updated to reflect current market prices, which improves accuracy but can add volatility.

In short, book value does not follow a single rule across all asset categories. Most assets rely on historical cost with adjustments, while some financial assets are measured at current fair value. This distinction is essential for interpreting what book value really tells you.

How Book Value Works for Liabilities

Liabilities on the balance sheet are also reported at book value, but the method of measurement depends on the type of obligation.

- Current liabilities: Accounts payable, wages payable, and other short-term obligations are typically recorded at the amount owed. Because they are settled in the near term, their book value usually matches closely with their settlement value.

- Long-term debt: Bonds and loans may be carried at the amount originally borrowed, adjusted for issuance discounts, premiums, and amortization over time. The carrying value often differs from the debt’s current market price.

- Lease liabilities: Under ASC 842, lease obligations are recorded at the present value of future lease payments. This approach reflects the long-term nature of lease commitments more accurately than older accounting rules.

- Contingent liabilities: Obligations such as pending lawsuits or guarantees are recorded only when they are both probable and reasonably estimable. As a result, some potential costs never appear on the balance sheet, even though they may impact the company later.

Because of these differences, the book value of liabilities may not equal their true economic burden. Some items approximate settlement value closely, while others reflect accounting conventions that diverge from market or eventual cash outflows.

Book Value of Equity

The book value of equity is calculated by subtracting total liabilities from total assets. It reflects the net worth of a company according to its accounting records. In theory, this is the amount shareholders would receive if all assets were sold at their recorded values and all obligations were settled.

To make the measure more practical, analysts often look at book value per share (BVPS). This is derived by dividing total equity by the number of shares outstanding. BVPS provides a per-share figure that can be compared directly with the stock’s market price.

When BVPS is significantly lower than the stock price, it suggests investors expect the company to generate strong future earnings or has valuable intangible assets not captured on the balance sheet. When BVPS is higher, it can point to a stock the market may be undervaluing or one that faces serious challenges.

Strengths of Book Value

- A Standardized Accounting Measure

Book value is anchored in formal accounting rules. Because it follows GAAP or IFRS, it provides a consistent framework that makes it possible to compare companies across industries and track performance over time. - Clarity in Asset-Heavy Industries

For banks, insurers, manufacturers, and other businesses with tangible assets like loans, property, and equipment, book value offers a reliable gauge. In these sectors, accounting values often approximate economic reality more closely than in asset-light companies. - Insight into Financial Leverage

By comparing the book value of assets with liabilities, analysts can quickly see how much of a company’s operations are financed by debt versus equity. This sheds light on risk exposure and financial resilience. - Stability Compared to Market Prices

Stock prices fluctuate daily with sentiment and speculation, but book value changes gradually as assets are depreciated, impaired, or added. This stability makes it a useful anchor during periods of market volatility. - A Basis for Valuation Ratios

Book value supports key metrics such as Price-to-Book (P/B) ratio and Book Value Per Share (BVPS). These ratios allow investors to compare market expectations with accounting fundamentals, providing insight into whether shares may be undervalued or overvalued. - Transparency into Balance Sheet Health

Because book value highlights the carrying amounts of assets and liabilities, it helps reveal shifts in capital allocation, changes in asset quality, or growing debt loads. It provides a clear window into how management decisions are shaping financial strength.

Limitations of Book Value

- Reliance on Historical Cost Accounting

Most assets are recorded at their original purchase price, adjusted for depreciation or impairment. This means book value may diverge significantly from economic reality. Real estate, natural resources, or long-held investments are often worth far more than their book values suggest. - Understatement of Intangible Assets

Internally developed intangibles such as brand strength, research capability, proprietary technology, or human capital are not recognized on the balance sheet. As a result, book value can drastically understate the worth of companies in knowledge-driven industries. - Backward-Looking by Nature

Book value captures what has already been recorded in the accounts, not what lies ahead. Markets, in contrast, look forward, pricing in growth prospects, competitive advantages, and earnings potential that book value cannot reflect. - Limited Relevance for Asset-Light Businesses

Service firms, software companies, and other asset-light models often generate most of their value from intangibles that never appear on the balance sheet. For these businesses, book value offers little insight into true worth. - Distortions from Accounting Rules

Differences in depreciation schedules, impairment testing, and write-down policies can make comparisons across companies misleading. Book value is consistent within a company, but it is not always consistent across industries or geographies. - May Lag Behind Market Conditions

In fast-moving sectors or during sudden economic shifts, book values adjust slowly. This can leave investors with outdated figures that do not capture current risks or opportunities.

Book Value vs Market Value

Book value represents the carrying amounts of assets and liabilities recorded under accounting rules. It is a snapshot rooted in historical cost and balance sheet conventions.

Market value represents what investors are willing to pay for a company’s shares today. It reflects collective expectations about future earnings, growth potential, and risks.

Why the Gap Matters

A significant difference between book value and market value can signal important insights:

- Market value below book value: This could suggest the stock is undervalued, offering a potential opportunity. It can also indicate hidden problems such as weak profitability, poor asset quality, or management concerns that are not obvious from the balance sheet.

- Market value above book value: Often points to strong growth expectations, valuable brand power, or intellectual property that accounting rules do not capture. Investors may be pricing in opportunities well beyond the company’s recorded net worth.

In practice, book value offers the baseline, while market value reveals what investors think the company is really worth. Comparing the two helps analysts judge whether optimism or caution is justified.

Key Takeaways

- Book value is the recorded value of assets and liabilities on the balance sheet.

- Tangible assets are listed at cost minus depreciation. Intangibles are recorded at acquisition cost and amortized.

- Liabilities are recorded at owed amounts, sometimes adjusted for discounts or premiums.

- Shareholder equity is the residual: assets minus liabilities.

- Book value is useful but limited, as it rarely matches true market value.